Second Citizenship as Business Protection

Why second citizenship has become the ultimate asset protection strategy for entrepreneurs navigating geopolitical risk?

The cardinal rule of sound investing—of building capital, of conducting business with any expectation of longevity—is diversification. Spread your assets across categories and geographies; structure your holdings with an eye toward resilience. But in our current moment, diversification increasingly extends to something more elemental: citizenship itself.

“May you live in interesting times,” goes the old saying—a Chinese curse, more precisely. We are, indisputably, living in interesting times, and this has consequences that reach well into the domains of law and commerce. It is no accident that commercial leases now routinely include clauses governing what happens if the building is destroyed by military action. The prudent businessperson might consider how similar risks apply elsewhere in their affairs. None of us wish to share the fate of Poland’s interwar industrialists, whose legacy survives mainly in the form of colorful stock certificates sold in antique shops.

This seems an appropriate moment to ask a discomfiting question: How does one safeguard one’s ability to operate in international commerce if Poland’s sovereignty were reduced to something resembling the Congress Kingdom—that nineteenth-century puppet state under Russian suzerainty—or worse, if passport renewal required an application to Mother Russia, or to a government-in-exile whose legal standing the world had quietly decided to ignore?

History offers instructive precedent. Though the international community expressed sympathy during the last global conflagration, Great Britain and the United States withdrew diplomatic recognition from the Polish government-in-exile in 1945. Within two years, only five nations—Spain, Cuba, Ireland, the Vatican, and Lebanon—still acknowledged its existence. The Vatican held out longest, finally withdrawing recognition in 1972.

The working hypothesis, then, is this: should comparable circumstances arise, Polish passports will be issued by whoever parks their tanks in Warsaw. Should that not be a Polish government, the world will protest, then forget, then acquiesce to the politics of fait accompli. Perhaps some nation will stage a theatrical gesture in the manner of nineteenth-century Turkey, which, having never recognized the partitions of Poland, began every audience with the Sultan by ritually inquiring, “Has the envoy from Lechistan arrived?” Such performances, however charming, do nothing to solve the practical difficulties of conducting business amid geopolitical upheaval.

The inability to obtain a new passport—to document one’s citizenship—renders a person functionally stateless: someone whom no nation, under its own laws, considers a citizen. Such individuals cannot open bank accounts or establish businesses. They cannot satisfy the anti-money-laundering procedures that bind not only banks but credit institutions, investment firms, and funds of every description. For an entrepreneur, these circumstances amount to commercial death.

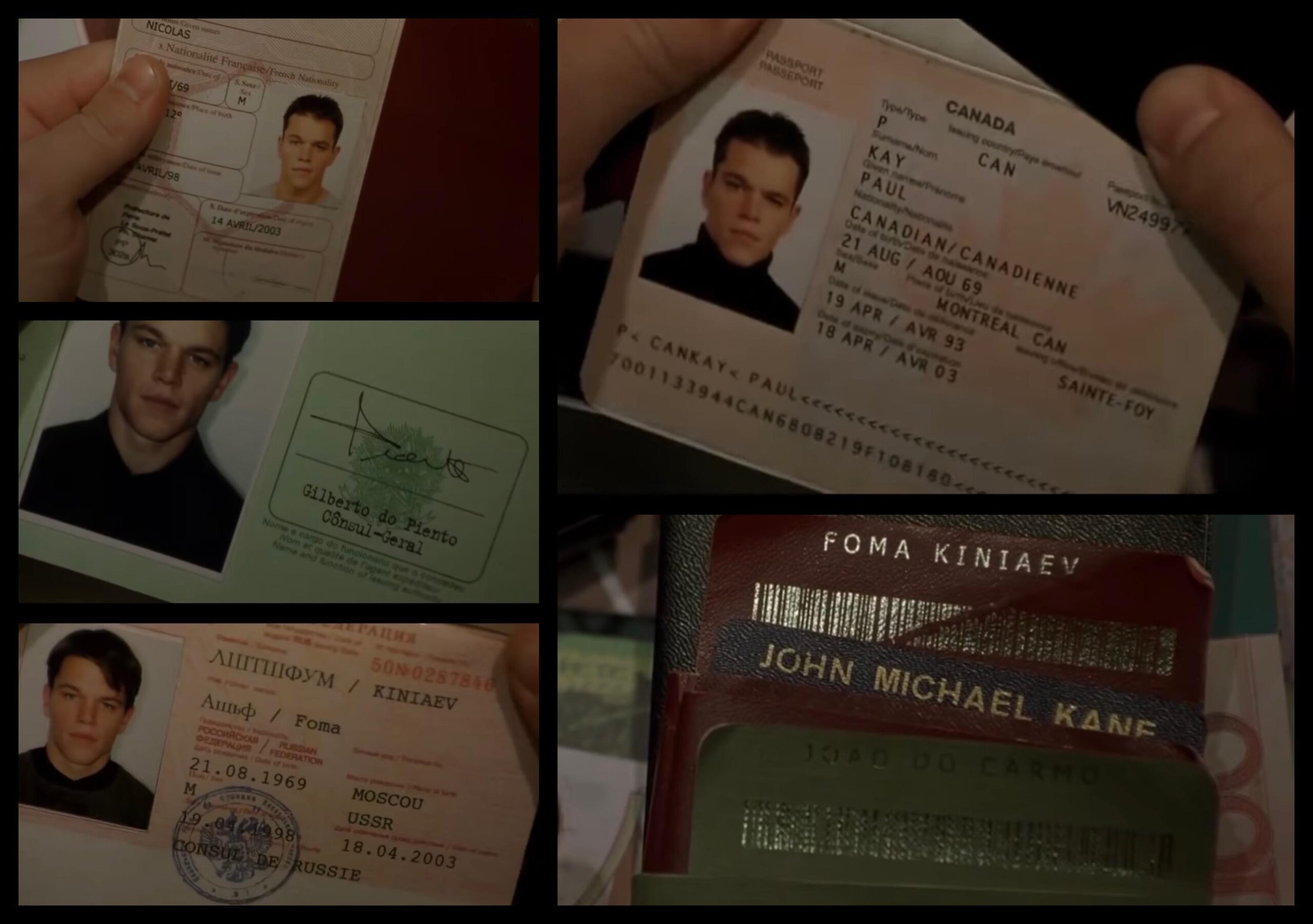

A solution exists, particularly for those engaged in international commerce: securing citizenship in a country that offers investment-based naturalization programs. These nations invite foreign capital into their industries and real estate markets as a means of stimulating their domestic economies, conferring citizenship upon investors in return. Such programs operate throughout the British Commonwealth—Dominica, Saint Lucia, the Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis, Grenada, Antigua and Barbuda—as well as in Europe (Montenegro, Malta, Turkey) and beyond.

Economic citizenship in another country eliminates political and economic risks while guaranteeing stability. A second passport means open borders, freedom to conduct global business, and the ability to diversify commercial activities across jurisdictions.

Similar reasoning appeals to individuals from countries where passport privileges function much as they did in communist Poland—as rewards dispensed in exchange for political loyalty.

Contemporary international law does not regard dual citizenship as problematic, nor do most national legal systems. The United States has permitted dual citizenship since the precedent-setting case of Talbot v. Janson in 1795, and American authorities maintain that loyalty to two nations can be reconciled—that one need not choose. An American citizen may naturalize elsewhere without risking the loss of U.S. citizenship.

Britain’s Nationality Act of 1948 removed restrictions on dual citizenship, as did Canada’s citizenship legislation of 1976. Under Polish law, a citizen holding another nationality enjoys identical rights and obligations toward the Republic as someone with Polish citizenship alone—a principle codified in Article 3 of the Polish Citizenship Act of April 2, 2009.

Acquiring a second citizenship as one element of a comprehensive asset-protection strategy—combined with geographic and asset-class diversification—can prove an effective means of ensuring business continuity through sudden geopolitical turbulence.

Most affluent entrepreneurs, however, concentrate their capital overwhelmingly in their domestic currency and home country, where they earn most of their income and maintain their family residence. A certain logic underlies this: familiarity with local conditions facilitates the management of capital in ways one understands, using asset classes one trusts. Yet it also means placing the family jewels in a single basket. However much confidence one has in one’s home economy, this concentration carries risk. Diversification merits consideration—foreign bank accounts in countries with well-developed private banking sectors, economic stability, traditions of judicial independence, respect for private property, and banking confidentiality. Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and the United States come to mind.

In the event of serious perturbations in world politics, Poland occupies what might be called a “crumple zone”—that brutal automotive metaphor for the part of a vehicle designed to absorb the energy of a collision, sacrificing itself to protect the passengers. The term captures, with uncomfortable precision, the realities of Poland’s geopolitical position.

The force of impact can be minimized. A second citizenship is one way to do it.

Robert Nogacki – licensed legal counsel (radca prawny, WA-9026), Founder of Kancelaria Prawna Skarbiec.

There are lawyers who practice law. And there are those who deal with problems for which the law has no ready answer. For over twenty years, Kancelaria Skarbiec has worked at the intersection of tax law, corporate structures, and the deeply human reluctance to give the state more than the state is owed. We advise entrepreneurs from over a dozen countries – from those on the Forbes list to those whose bank account was just seized by the tax authority and who do not know what to do tomorrow morning.

One of the most frequently cited experts on tax law in Polish media – he writes for Rzeczpospolita, Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, and Parkiet not because it looks good on a résumé, but because certain things cannot be explained in a court filing and someone needs to say them out loud. Author of AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto: Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator. Co-author of the award-winning book Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy (Security of a Modern Company).

Kancelaria Skarbiec holds top positions in the tax law firm rankings of Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Four-time winner of the European Medal, recipient of the title International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.

He specializes in tax disputes with fiscal authorities, international tax planning, crypto-asset regulation, and asset protection. Since 2006, he has led the WGI case – one of the longest-running criminal proceedings in the history of the Polish financial market – because there are things you do not leave half-done, even if they take two decades. He believes the law is too serious to be treated only seriously – and that the best legal advice is the kind that ensures the client never has to stand before a court.