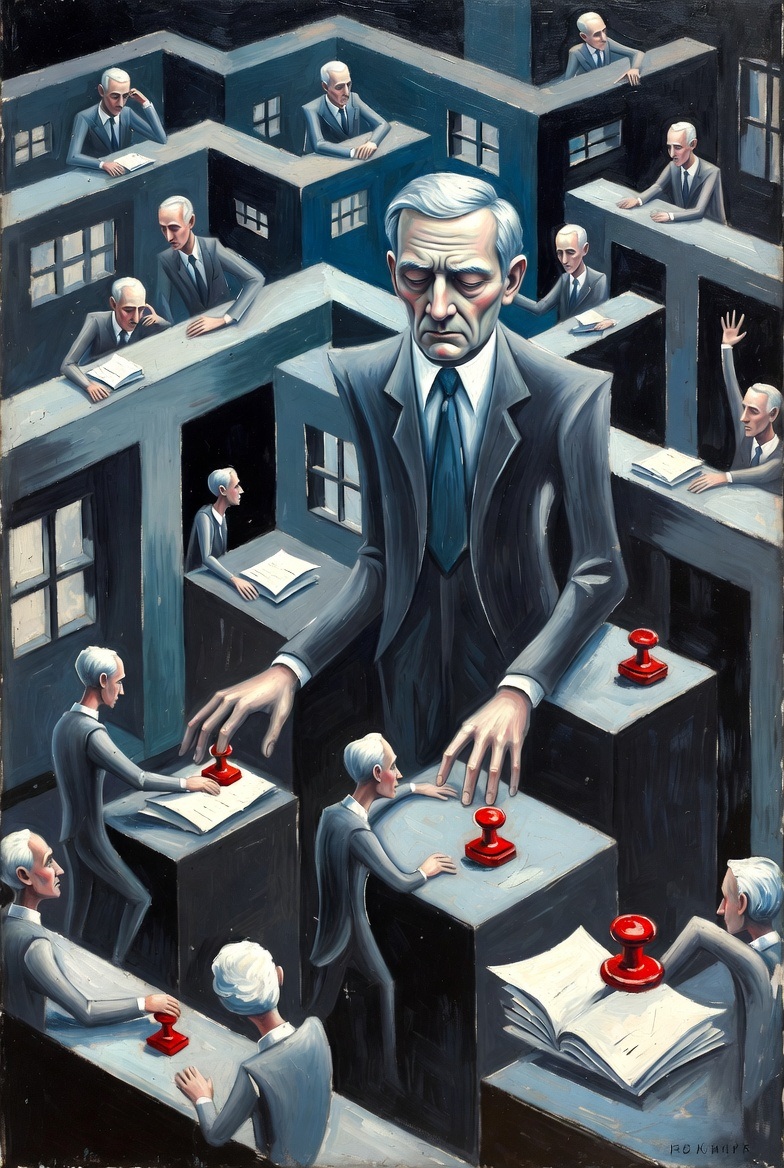

Epitaph for Swiss Banking Secrecy

How a hundred-and-four-million-dollar reward to a bank informant marked the end of an era—and what rose from its ashes thirteen years later

In September of 2012, the Internal Revenue Service paid a hundred and four million dollars to Bradley Birkenfeld, a Swiss banker who had handed over data on thousands of American citizens hiding money at UBS. No reasonable person would expect bankers to remain loyal to their clients when faced with a choice between prison and a nine-figure windfall.

At the time, the payout seemed like a symbolic death knell for a certain kind of banking. Thirteen years on, we know it was more than symbol. Traditional Swiss banking—built on a discretion that bordered on silence—has indeed come to an end. But something unexpected has grown from its ruins: a sector that is financially stronger than ever, managing record assets exceeding nine trillion Swiss francs.

The story deserves careful examination, because it illustrates a broader phenomenon: how institutions can survive the loss of what appeared to be their fundamental competitive advantage.

I. Why the Swiss?

Switzerland is a country of extraordinary political and economic stability. Setting aside sporadic conflicts between cantons, the Swiss army has not participated in a war for five hundred years. (Cynics suggest this explains its specialty in producing the world-famous pocketknife.) Switzerland has never experienced runaway inflation, high unemployment, nationalization of private assets, or rule by political extremists.

Even the radical religious views of John Calvin, who led an influential Protestant community in Geneva during the sixteenth century, ultimately fostered the development of cantons as stable, democratic societies governed by prosperous citizens. Such people naturally adopted conservative political courses, treating diligence and enterprise as virtues.

Above all, Switzerland was a land of order and law. As James Joyce reportedly observed, Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich is so clean you could lick vegetable soup off it. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it was the only place of its kind where fair treatment—equal under the law and independent of political circumstances—could be expected by Lenin in Genevan exile, by Jews hiding savings from the Nazis, and by Nazis stashing gold plundered from occupied Europe in Swiss vaults.

For all these reasons, depositing money in Switzerland gave wealthy foreigners rational grounds for hoping that their funds would remain untouched by any crisis.

In the nineteen-thirties, an additional factor emerged: Swiss banking secrecy, based on the rigorous provisions of the Banking Act of 1934. The conviction took hold that Switzerland, pursuing its policy of political neutrality, would not bend to any pressure aimed at seizing accounts opened for foreigners.

This optimism stemmed from Swiss conduct toward the socialists who came to power in France and Germany during that decade. In 1932, Swiss banks successfully resisted the French government of Édouard Herriot, which demanded the return of wealthy Frenchmen’s savings. A year later, Switzerland refused to yield to National Socialist legislation that prescribed the death penalty for failing to disclose foreign bank accounts to the government.

II. The Black-P.R. Campaign

The following decades brought continued, steady growth for banks specializing in managing the assets of the affluent. Swiss banking became a permanent fixture in popular culture—in films and thrillers, villains and spies can always be identified by their Swiss accounts.

In Frederick Forsyth’s “The Day of the Jackal,” the assassin hired to kill General de Gaulle naturally requests that his half-million-dollar fee be deposited in a Swiss bank. In “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” Lisbeth Salander, posing as an associate of the fugitive financier Hans-Erik Wennerström, effortlessly withdraws two billion dollars in bonds from a Zurich account, freshly wired from a bank in the Caymans. Auric Goldfinger, James Bond’s adversary in the third 007 film, reportedly keeps twenty million pounds in gold bars “in Zurich, Nassau, and Panama.” Swiss accounts also belong to other spies—Jason Bourne, for instance.

Some of these pop-cultural notions bear a certain resemblance to reality, but others are completely detached from fact. In many cases, they diverge so far from the truth that one wonders whether they constitute a deliberate disinformation campaign.

It is certainly true that in the nineteen-sixties and seventies it was relatively easy to deposit money in Switzerland using false identity documents. But that was true everywhere in the world at the time. If Switzerland was discussed particularly often in this context, it was solely because it was an especially attractive destination for such deposits—not because the Swiss were especially active in facilitating them.

It is also true that a large portion of “old” assets in Swiss banks, deposited in the previous century, went undeclared by taxpayers in their home countries, because they felt confident that Swiss banking secrecy would serve as an effective barrier against the taxman. The conduct of Swiss bankers in supporting such practices can only be described as reckless and shortsighted—something for which the entire banking system would later pay dearly.

On the other hand, the account-opening procedures depicted in popular films are completely absurd and unrealistic. Many Polish clients are astonished by the volume of questions they receive from banks during the account-opening process, and subsequently in connection with larger financial operations. At the relationship-initiation stage, every bank seeks a thorough understanding of the client’s business and the source of funds—to verify that the activity is not a front for money laundering. Questions may extend to the political activities of grandparents or unfavorable press coverage from years past.

That is why the fictional Lisbeth Salander would never have withdrawn two billion dollars from a Zurich account under the circumstances depicted in the novel. In reality, such a transaction would have required weeks of painstaking documentation to establish the legality of funds deposited in the Caymans, without which a Swiss bank would neither accept two billion euros nor permit their withdrawal. If the beneficiary were the subject of criminal proceedings, the bank would likely withdraw from the transaction even if the documentation were in order.

Particularly absurd are the operating principles of the fictional Depository Bank of Zurich in Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code.” According to Brown’s vision, the bank offered “the full range of anonymous services in the tradition of the Swiss numbered account”—with branches in Zurich, Kuala Lumpur, New York, and Paris. “The bank had recently expanded its services to offer anonymous computer-generated code source deposit boxes—with digital anonymity security.”

In reality, precisely to prevent such scenarios, safe-deposit boxes are always linked to bank accounts, and account opening is preceded by beneficiary-identification procedures.

III. The Onset of International Pressure

From the mid-nineteen-nineties, Swiss banks came under increasing pressure from the so-called “international community”—in practice, the socialist parties governing most European Union countries and American Democrats.

Spin doctors for this marketing campaign deftly placed “statistics” and “reports” in the press, from which it was learnedly demonstrated that the existence of Swiss banks caused cows in the Third World to stop giving milk, children to starve, and widows to mourn their husbands—because billions of dollars were flowing to tax havens, whose owners, for some reason, should be compelled to keep their money elsewhere. Preferably in countries with high taxes and extensive welfare systems, so that the money could be taken from them and given to “the poor”—that is, to the state administrations of countries sponsoring the entire campaign.

The Tax Justice Network continues to excel in publishing such analyses, led by a group of “concerned activists” associated with the anti-globalization movement, liberation theology, and the Greens.

In reality, this “scientific” analysis of the effects of Swiss banking is as absurd as its media image, because it rests on the assumption that money recorded in Swiss bank accounts disappears from the economies of origin. In fact, Swiss bankers typically recommend that their clients reinvest these funds in government and corporate bonds or equities, or disburse them to countries of origin through Lombard loans. Consequently, money recorded in Swiss accounts is available for investment and consumer spending on the same basis as funds held in local banks, and the entire methodology underlying such calculations is fundamentally flawed.

Independent analyses confirm these reservations. The Tax Justice Network’s methodology classifies approximately half of all foreign bank deposits worldwide as “abnormal,” suggesting that the very concept of “abnormal” has been poorly defined. The data the organization uses does not distinguish corporate deposits from individual deposits, and many offshore deposits have entirely legitimate business purposes: trade financing, currency transactions, liquidity management for multinational corporations.

IV. The Deployment of Intelligence Services

As economic conditions in developed countries deteriorated, the so-called “international community” moved from verbal aggression to direct action against individual banks. Between 2008 and 2012, a series of skirmishes unfolded between the intelligence services of high-tax countries and banks in Switzerland and Liechtenstein—which the latter lost ignominiously.

In 2008, Heinrich Kieber, an employee of LGT Bank in Liechtenstein, sold data on fifty-eight hundred clients to German intelligence services. They not only paid him nearly four million euros but also helped him obtain a new identity, under which he currently hides from Liechtenstein authorities, who have posted a ten-million-dollar reward for bringing him before a local court. The incident was a watershed: for the first time, the government of a major European country ostentatiously paid a bank employee for breaking the law and helped him evade justice.

That same year, Rudolf Elmer, who had headed the Caribbean operations of the Swiss bank Julius Baer, passed data on numerous accounts to Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks. Assange published the materials online, revealing internal correspondence among bank employees that indirectly disclosed account holders’ personal data and transaction histories. In 2011, Elmer and Assange released a second, more detailed trove on WikiLeaks.

Elmer’s case proved legally interesting: in 2016, the Zurich Cantonal Supreme Court cleared him of violating banking secrecy, arguing that he had worked for a Cayman Islands subsidiary and was therefore not subject to Swiss law. The judge nevertheless called him “not a whistleblower, but an ordinary criminal.” The embarrassment lay in Elmer’s exploitation of this legal loophole to remain free.

In December, 2008, the management of HSBC’s Swiss bank learned of a data theft by Hervé Falciani, an I.T. employee. The leak ultimately involved data on more than a hundred and thirty thousand accounts—”the largest banking data leak in history.” Falciani fled to France, where he handed over the data to local intelligence services, which shared it with other countries; Britain alone received information on six thousand clients. In 2015, a Swiss court sentenced Falciani in absentia to five years in prison.

All these cases severely damaged the reputation of Swiss banks and shattered the taboo associated with the quality of their data protection. The banks proved completely unprepared to withstand such aggressive actions by the intelligence services of larger, more powerful neighbors.

V. Open War with the United States

These events, however, were merely a prelude to a direct financial assault on Swiss banks, which also ended in complete defeat.

On February 18, 2009, UBS reached a settlement with the American tax authorities, agreeing to pay seven hundred and eighty million dollars in penalties for participating in a conspiracy against the United States government—that is, for concealing the assets of American taxpayers. UBS subsequently agreed to hand over data on more than forty-four hundred American clients to the I.R.S.

Given that many of these clients had been actively encouraged by UBS bankers to commit offenses against the I.R.S., the bank’s conduct—without in any way excusing the clients themselves—must be regarded as exceptionally base and unworthy of an institution of public trust.

In May, 2014, the second major Swiss bank, Credit Suisse, pleaded guilty and agreed to pay $2.6 billion (later reduced to $1.3 billion) for helping thousands of American clients evade taxes.

Credit Suisse’s history demonstrates, however, that some institutions cannot learn from their own failures. In May, 2025, Credit Suisse Services AG—by then absorbed by UBS—pleaded guilty again, this time for violating the 2014 settlement. The bank had helped conceal more than four billion dollars in at least four hundred and seventy-five accounts between 2010 and 2021. The fine was five hundred and eleven million dollars. Bankers had falsified documents, processed fictitious gift documentation, and serviced more than a billion dollars in accounts without any tax-compliance documentation.

In total, HSBC, Credit Suisse, and Julius Baer handed over data on ten thousand of their own employees to American authorities. It is difficult to imagine a more humiliating surrender, one that must have devastated employee morale.

In December, 2023, Banque Pictet joined the list of the penalized, pleading guilty to conspiring to defraud the I.R.S. and agreeing to pay $122.9 million. The bank had helped American taxpayers hide more than $5.6 billion between 2008 and 2014, employing “various tactics to facilitate concealment,” including opening offshore entities, permitting withdrawals below the ten-thousand-dollar threshold, and offering “hold-mail account” services.

The only bank that refused to yield to American demands was Wegelin & Co. Privatbankiers, founded in 1741—the oldest private bank in Switzerland. But as a result of its dispute with American prosecutors, the owners transferred the business to Notenstein Private Bank, which they sold to the Raiffeisen group.

Wegelin effectively ceased operations. In the course of proceedings before a Manhattan court at the I.R.S.’s behest, Judge Jed Rakoff declared the entire bank a “fugitive,” accused it of “disrespect for the United States government,” and suggested arresting the partners. (As a traditional private bank, Wegelin was a limited partnership in which partners bear personal liability for the bank’s obligations.) In January, 2013, the bank pleaded guilty and agreed to pay $57.8 million for helping more than a hundred American citizens conceal $1.2 billion.

As the prosecutor Preet Bharara observed, this was “the first foreign bank to plead guilty in a tax-evasion case in the United States” and “a turning point in our efforts.” The end of Wegelin’s three-century history sent a clear message to the market: any bank that dares to defy the I.R.S. will face extinction—even one seemingly unconnected to the American market.

VI. The Arab Spring and the Primacy of Politics over Law

Under mounting international pressure, Swiss banks acknowledged the political primacy of the United States and, in critical situations, followed directives from Washington. Their response to the Arab Spring and the fate of deposed leaders’ assets is telling.

In May, 2011, the Swiss Foreign Minister, Micheline Calmy-Rey, announced the freezing of approximately 830 million Swiss francs in assets linked to deposed leaders: 360 million for Muammar Qaddafi of Libya, 410 million for Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, 60 million for Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia. The history of the Qaddafi family’s assets demonstrates that Swiss banks had accepted the primacy of political considerations over the rule of law.

In writing this, I do not claim that the Qaddafi family’s fortune was acquired legally—only that no one examined its legality. The decision to freeze the assets and subsequently transfer them to the National Transitional Council was not preceded by any investigative process requiring years of painstaking audits. It is difficult, moreover, not to connect the timing of this decision with the political situation. Why did Swiss banks raise no questions about the legal origin of these funds during the long decades when they were being deposited, but only when Qaddafi’s armies began losing on the battlefield?

This represents a stark contrast to the unbending posture of Swiss bankers in the nineteen-thirties, when they faced aggressive demands from Nazi Germany and socialist France—a posture that built the reputation of reliable Swiss banking.

The weakness Swiss banks displayed toward American authorities encouraged other countries to take similar action. In July, 2012, French police conducted searches at UBS offices in Lyon, Bordeaux, and Strasbourg, as well as at the homes of some employees. German police knocked on the doors of many Credit Suisse clients. A month later, German investigators searched the homes of Julius Baer clients. Whatever the banks’ spokespeople may say, this was a genuine hunt for Swiss-bank clients, conducted with only token resistance from the banks themselves and Swiss authorities.

VII. The Formal End of Banking Secrecy (2018)

Everything described above, however, was merely a prelude to the real end, which came in September, 2018, when Switzerland began the automatic exchange of tax information with more than a hundred countries under the Common Reporting Standard developed by the O.E.C.D.

This was the formal end of traditional banking secrecy for foreign clients.

From that point on, Swiss banks automatically transmit the following information to the tax authorities of clients’ countries of origin: name, surname, and address; country of tax residence; tax-identification number; date of birth; total account value; interest, dividends, and sales proceeds; all significant financial flows.

The exchange is reciprocal—Switzerland also receives information on Swiss citizens’ accounts abroad.

Another historic change came in June, 2024, when Switzerland and the United States signed a new FATCA Model 1 agreement, effective January 1, 2027. For the first time, the United States will transmit account data to Switzerland—making the exchange mutual rather than one-sided.

An important distinction should be noted, however: while banking secrecy has ended for non-residents, it continues to apply to Swiss citizens subject to Swiss taxation. Article 47 of the 1934 Banking Act still provides criminal penalties for violating banking secrecy—up to three years’ imprisonment for intentional violations, up to five years if the perpetrator derived financial benefit, and fines up to two hundred and fifty thousand francs.

In recent years, this law has become a source of controversy. Swiss authorities initiated the first-ever criminal proceedings against a journalist for publishing the “Suisse Secrets” exposé on suspicious accounts. The U.N. Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression, Irene Khan, called the law “an example of the criminalization of journalism.” Article 47 protects banking information even when it serves to reveal crimes—if the disclosure comes from someone bound by secrecy.

Further erosion of traditional protections came on January 1, 2024, when amendments to the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure took effect, abolishing banking secrecy as grounds for sealing documents in criminal proceedings. Banks now rarely have a legally protected interest in preventing the disclosure of banking documents in criminal cases. The Swiss Federal Supreme Court confirmed this interpretation in a September, 2024, ruling.

VIII. The Great Consolidation

The consequences of all these changes proved dramatic for the sector—though not in the way one might have expected.

The number of private banks in Switzerland fell from a hundred and sixty in 2010 to approximately eighty by the end of 2025. Experts predict that around fifty institutions will remain by 2030. The most recent consolidation wave, in 2024-25 alone, brought nine major transactions in ten months.

The largest was UBS’s acquisition of Credit Suisse in 2023—a transaction valued at 1.6 trillion Swiss francs that redefined the entire sector. But smaller deals also transformed the market: Union Bancaire Privée acquired Société Générale Private Banking (Suisse), with assets of fifteen billion francs; Safra Sarasin bought Saxo Bank, with eighty-eight billion in assets; Vontobel purchased IHAG Privatbank.

The causes of consolidation are multiple. Regulatory costs associated with implementing Basel III require significantly higher capital. Investments in A.I., blockchain, and automation are too expensive for small banks. Rising compliance costs for AEOI, FATCA, and anti-money-laundering regulations squeeze margins. Competitive pressure and years of low interest rates have further constrained profitability. Small banks without clear specialization simply cannot survive.

For clients, this means a narrower choice of institutions, increased market concentration (with attendant systemic risks), and potentially higher fees—but also better technological services and greater financial stability among surviving players.

IX. The New Positioning: From Secrecy to Compliance

Here we arrive at a surprising paradox. Despite losing what appeared to be its fundamental competitive advantage—banking secrecy—the Swiss private-banking sector has not merely survived; it has thrived.

Assets under management have exceeded 9.2 trillion Swiss francs—a record level. Growth in 2024 reached 10.6 per cent. Switzerland still manages approximately a quarter of all cross-border assets worldwide. Private-banking revenues reached 21.4 billion francs, up from 20.5 billion the previous year.

How is this possible?

Switzerland can no longer compete on banking secrecy, so it has changed its positioning. Instead of discretion, it offers regulatory stability—FINMA as one of the world’s most rigorous supervisors. Instead of concealing assets, it offers expertise in wealth management—advanced services unavailable elsewhere. It offers multi-currency accounts and access to global markets. It offers political and economic stability—five hundred years without war is a difficult argument to refute. It offers robust legal frameworks with creditor protection and regulatory predictability. It offers excellent technological infrastructure and a global network.

Know Your Customer and due-diligence procedures, once seen as obstacles, have become competitive advantages. Clients know that money deposited in a Swiss bank has undergone rigorous verification of its origin. This means the bank will not accept funds that might expose the institution to regulatory problems—and will therefore also reject other clients’ funds that might threaten the stability of the entire system.

Identity verification encompasses not only official documents but often biometrics as well. Client risk classification divides clients into low-risk categories (O.E.C.D. citizens with stable income sources), medium risk (business clients, certain jurisdictions), and high risk (politically exposed persons, countries with weak A.M.L. regulations, high-risk industries). For this last category, enhanced due diligence applies—additional verification of fund sources, screening against financial-crime databases, periodic reviews every six to twelve months, and verification of beneficial owners.

In 2023, more than eight thousand suspicious-activity reports were filed in Switzerland with MROS, the country’s money-laundering-reporting office. FINMA supervision employs a risk-based approach, with more intensive oversight of systemically important institutions, regular audits, on-site inspections, and penalties for non-compliance—including license revocation and public sanctions.

X. Alternative Jurisdictions

The 2012 article correctly predicted that “most clients are flowing toward the Caymans, Hong Kong, and Singapore.” This has proved accurate—but with an important caveat.

All these jurisdictions are now covered by CRS/AEOI, so none offer actual “secrecy” in the tax sense. Differences now concern primarily tax efficiency (varying territorial systems), banking-service quality, market access (Hong Kong as a gateway to China, Singapore as a Southeast Asian hub), and political stability.

Singapore offers no tax on foreign income, high privacy, and rigorous MAS supervision—but also higher minimum thresholds. Hong Kong has zero tax on offshore income, but political developments since 2020 have raised concerns among some clients. The United Arab Emirates, particularly Dubai, offer competitive taxation and growing regulatory quality, but a relatively brief history as a financial center. Mauritius charges no tax on foreign income and provides high privacy with relatively low entry thresholds.

The crucial lesson, however, is this: in the era of AEOI/CRS, choosing a banking jurisdiction should be based on legitimate advantages—operational efficiency, market access, stability—not on hopes of hiding assets. No serious jurisdiction any longer offers actual secrecy for non-residents.

XI. The Future of Private Banking

The situation of Swiss-bank clients who, at the urging of their bankers, illegally concealed their income is now dire. All indications suggest that the traditional Swiss-banking model has come to an end.

This does not, however, mean the end of private banking as such. Clients seeking substantial discretion from their bankers are turning to European financial centers that acted more prudently than Swiss bankers in previous decades—Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, or Monaco. But most flows are heading to Singapore and Hong Kong.

In each of these locations, however, one should expect careful scrutiny of whether a client’s funds derive from legal sources. This is hardly surprising: the consequences faced by Swiss banks and their clients demonstrate the long-term superiority of legal forms of international tax optimization over illegal tax evasion.

For Switzerland itself, the future looks surprisingly optimistic—provided the sector maintains its current course. Experts predict further consolidation, from approximately eighty banks to around fifty by 2030. Survival will require continued investment in technology—artificial intelligence, blockchain, automation—and specialization in market niches. Generalists will be consolidated or fall out of the market.

Challenges include a shortage of qualified compliance specialists and relationship managers, growing cybersecurity threats, and the need to adapt to new regulations—including CRD VI and the Crypto Asset Reporting Framework, which extends information exchange to digital assets.

Positive trends are also visible, however. Banks that survive will be stronger and better capitalized. New business models will emerge: family offices, multi-family offices, fintech firms. Specialization in niches—E.S.G., sustainable finance, cryptocurrencies—will create new sources of competitive advantage.

XII. Conclusions

Swiss banks—and their clients who, at the banks’ encouragement, illegally concealed their income—now face a reckoning. The traditional Swiss-banking model has reached its end.

The lesson for potential clients is straightforward. In the era of global tax transparency, there are no longer places where one can “hide” wealth. There are only places where one can manage it legally and efficiently. And Switzerland—paradoxically—remains one of the best such places in the world. Not despite the loss of banking secrecy, but because it adapted to the new reality.

The story of Swiss banking secrecy is, ultimately, a story about institutional resilience and the limits of competitive advantage. For decades, discretion was everything. Now discretion is nothing—and yet the Swiss, with characteristic pragmatism, have discovered that what they were really selling all along was competence, stability, and trust. The secrecy, it turns out, was merely the wrapping.

This article was updated in January, 2026, based on an original version from 2012.

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.