Illegible but Valid? On the Form of Signature in Polish and International Law

Every individual signs documents differently. Some carefully inscribe each letter of their surname; others produce artistic flourishes resembling an electrocardiogram; still others confine themselves to a few vigorous strokes of the pen. The question naturally arises: are all these forms legally equivalent? Can an illegible signature be valid? And what of the paraph—can it substitute for a full signature?

These questions, seemingly mundane, carry fundamental significance for the security of legal transactions. Answering them requires examination of both Polish jurisprudence and international standards, which have acquired particular importance in an era of digitalization and global commerce.

I. Defining the Signature: The Search for Legal Meaning

A. The Absence of a Statutory Definition

Perhaps surprisingly, neither the Polish Civil Code, nor the Law on Bills of Exchange, nor any other Polish statute contains a definition of “signature”. As the Supreme Court observed in its landmark resolution of seven judges dated December 30, 1993 (III CZP 146/93): “Current legislation contains no express indication of what the content of a signature should be or how it should be executed.”

This absence of definition is not accidental. The legislature deliberately preserved judicial flexibility in assessing whether a given graphic mark fulfills the functions of a signature. This approach finds parallels in the legal systems of other states and in instruments of international law.

B. The Functions of Signature as the Key to Understanding Its Essence

Given the absence of a statutory definition, the validity of a signature must be assessed by reference to the functions it serves in legal transactions. Legal doctrine identifies, in particular:

- The identificatory function—indicating the person making the declaration of will

- The confirmatory function—expressing certainty regarding the participation of a given person in the act of signing

- The associative function—linking the signatory to the content of the document

The UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Signatures of 2001, while not defining these functions expressly, incorporates criteria for the reliability of electronic signatures that reflect the traditional role of signatures in identifying the person, confirming the act of signing, and establishing connection with the document’s content.

The Polish Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 8, 2012 (III CSK 209/11), developed this conception further, stating that “a signature cannot consist of arbitrary graphic marks, but must comprise letters forming, in principle, the name and surname of the person who signs.”

II. Signing on Behalf of Another: The Principle of Signatures in Common Law

A. When an Agent May Write Another’s Name

Consideration of signature form leads to an even more fundamental question: must a signature be affixed personally? When a document requires the signature of “John Smith,” must John Smith himself take up the pen—or is it sufficient that a person authorized by him writes his name?

Under Polish law, a document executed in such manner would not be legally effective. However, in private international law there exists the classical principle of locus regit formam actus (lex loci actus), according to which the form of a legal act may be governed by the law of the place where it was performed.

In common law systems, the answer evolved over centuries and took the form of the so-called “principle of signatures”—the rule that a person may “sign” a document not only with his own hand, but also through the hand of another who has been authorized to do so or who acts in his presence and at his direction. Moreover, a document signed in this manner is legally equivalent to one signed personally.

B. Historical Foundations

The roots of this principle extend at least to Lord Lovelace’s Case (1632), in which it was held that “if one of the officers of the forest put one seal to the Rolls by assent of all the Verderers, Regarders, and other Officers, it is as good as if every one had put his several seal.”

In Nisi prius coram Holt (1701), Chief Justice Holt ruled that the holder of a bill of exchange could orally authorize another person to endorse the bill in his name—”and when that is done, it is the same as if he had done it himself.” Of fundamental importance was Combe’s Case (1614), in which Lord Coke explained that an agent acting under a power of attorney should act in the name of the principal and sign documents with the principal’s name, not his own.

From these precedents emerged a principle of considerable practical consequence: when an authorized agent signs a document with the principal’s name, that signature is, in the eyes of the law, the signature of the principal, not of the agent. As an American court stated in Patterson v. Henry (1830): “When the name of the principal is subscribed by his agent, the former is liable in his own name on the contract, because, in law, the signature is his.”

The historical precedents discussed herein are cited from the 2005 Memorandum of the White House Office of Legal Counsel, entitled Whether the President May Sign a Bill by Directing That His Signature Be Affixed to It, which remains publicly available on the White House website.

I must note one source limitation: the formula quoted above from Patterson v. Henry, 27 Ky. 126 (1830) is drawn from the OLC Memorandum; however, neither the text of this decision nor any contemporary edition of the Kentucky Reports containing such a ruling could be located in available case collections. For this reason, I treat this case not as an independently verified precedent, but rather as an example of historical reconstruction undertaken by the Memorandum’s authors—significant for illustrating the general principle, yet requiring caution in precise citation.—R.N.

C. Applications and Extensions

This principle found application in diverse contexts. Agents could endorse bills of exchange in their principals’ names. Attorneys could execute and sign deeds on behalf of property owners. The Statute of Frauds of 1677 expressly provided that contracts subject to the writing requirement could be signed by a party “or by her agent in that behalf lawfully authorised.” Wills could be signed by another person in the presence and at the express direction of the testator.

Particularly interesting is the distinction between written authorization and action in the principal’s presence. For ordinary (unsealed) instruments, oral authorization of the agent sufficed—even authorization implied from circumstances. For sealed documents (deeds), authorization of equal formality was generally required. An exception existed, however: even without formal power of attorney, an agent could sign and seal a document if doing so in the principal’s presence and at his direction. As Justice Story explained: “Where the principal is present, the act of signing and sealing is to be deemed his personal act, as much as if he held the pen, and another person guided his hand and pressed it on the seal.”

This principle has survived into modern times and found application even at the highest levels of government. In the 2005 Office of Legal Counsel opinion cited above, it was confirmed that the President of the United States may “sign” a bill within the meaning of Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution by directing a subordinate to affix the President’s signature using an autopen—a device that mechanically reproduces a signature. The crucial distinction is between the decision to sign (which must remain personal and cannot be delegated) and the technical act of affixing the signature (which may be performed by another at the President’s express direction).

As early as 1824, Attorney General William Wirt confirmed that the Secretary of the Treasury could “sign” official documents using a stamp or copper plate bearing his name, provided he maintained control over the process and acted consciously. “The adoption and acknowledgment of the signature, though written by another, makes it a man’s own,” Wirt explained.

D. The Continental Perspective

For the Polish jurist, this principle may appear foreign, even dangerous. Polish law recognizes the institution of agency (pełnomocnictwo), but the agent acts in the name of the principal while signing with his own name, adding an indication that he acts on another’s behalf—rather than signing with the principal’s name as the principal.

This difference has deep systemic roots. In the continental tradition, the signature serves primarily an identificatory function—it indicates who physically made the declaration of will. In the common law tradition, emphasis falls on the authenticating function—the signature confirms that a specified person assumes responsibility for the document’s content, regardless of whose hand guided the pen.

This divergence in perspective explains why, under English law, a maritime broker may sign an email with the name “Guy” and thereby bind his principal to a guarantee worth tens of millions of dollars—while under Polish law, such practice would raise serious doubts as to the signature’s validity.

III. Legal Requirements for Signatures: Comparative Analysis

A. The United Kingdom: When an Email Footer Becomes a Signature

The case of Neocleous v Rees [2019] EWHC 2462 (Ch) resolved the question whether an automatically generated email footer could satisfy the signature requirement prescribed by Section 2 of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989.

The defendant, Ms. Rees, owned a small parcel of land with a jetty on Lake Windermere, accessible only by crossing the claimants’ property. A dispute over right of way came before the First Tier Tribunal. On the eve of the hearing, the parties reached a settlement—the claimants were to acquire the disputed parcel for £175,000. The terms were agreed by telephone and subsequently confirmed by email exchange between the parties’ solicitors.

The email from Ms. Rees’s solicitor, David Tear, concluded with the words “Many thanks,” after which Microsoft Outlook automatically inserted a footer containing his name, position, and the phrase “For and on behalf of AWB Charlesworth Solicitors.” When Ms. Rees attempted to withdraw from the settlement, she argued that an automatically generated footer did not constitute a “signature” within the meaning of the statute.

Judge Pearce rejected this argument. Referring to the contemporary understanding of the concept of signature, he observed: “Many an ‘ordinary person’ would consider that what is produced when one stores a name in the Microsoft Outlook ‘Signature’ function with the intent that it is automatically posted on the bottom of every email is indeed a ‘signature.'”

The court identified three elements decisive for the validity of a signature so affixed. First, the footer could appear in the email only because someone consciously configured it—entering the data and activating the appropriate settings. Second, the sender knew that his identifying information would be attached to the message. Third, the manual typing of the words “Many thanks” immediately before the automatic footer demonstrated an intention to connect his name with the document’s content—an intention to authenticate.

This ruling exemplifies the functional approach to the concept of signature dominant in English law: what matters is the intention to authenticate the document, not the graphic form of the mark. At the same time, the case serves as a warning to practitioners—routine correspondence may unexpectedly transform a non-binding exchange into an enforceable contract.

B. Golden Ocean Group v Salgaocar: A Chain of Emails as Contract

The case of Golden Ocean Group Ltd v Salgaocar Mining Industries PVT Ltd [2012] EWCA Civ 265 stands as one of the most significant precedents concerning the form of guarantee contracts in the age of electronic communication. The dispute concerned approximately $54 million—damages for breach of a ten-year charter of a newbuilding Capesize bulk carrier of 176,000 tonnes deadweight.

Negotiations proceeded in the manner typical for the shipping market: through email exchange between brokers. Guy Hindley of the London firm Howe Robinson represented the Indian conglomerate Salgaocar Mining Industries and its Singaporean chartering subsidiary, Trustworth. Terms were agreed incrementally—successive messages modified earlier arrangements using the “accept/except” method, without repeating the full contract terms each time. The crucial email of February 21, 2008, which according to the shipowners finalized both the charter and the guarantee, Hindley signed only with his first name: “Guy.”

When Salgaocar Mining Industries refused to honor the guarantee, it raised a formal argument: Section 4 of the Statute of Frauds 1677 requires that a contract of guarantee be in writing and signed by the guarantor or his representative. The defendant contended that this requirement could be satisfied only by a single document containing all contract terms, not a dispersed chain of correspondence. Furthermore, the argument continued, the name “Guy” alone constituted at most a greeting, not a signature.

The Court of Appeal rejected both contentions. Lord Justice Tomlinson stated that under conditions of contemporary commercial practice, there was no reason to limit the number of documents in which a contract of guarantee may be contained. The Statute of Frauds was intended to prevent disputes over the content of oral promises—this purpose is served equally effectively by a sequence of emails as by a single document, provided the whole is properly authenticated.

As to signature, the court adopted a functional approach. The parties agreed that an electronic signature in the form of a name, initials, or even a pseudonym could suffice—the court did not question this position. In his judgment, Lord Justice Tomlinson wrote: “Mr Hindley put his name, Guy, on the email so as to indicate that it came with his authority and that he took responsibility for its contents. It is an assent to its terms. I have no doubt that that is a sufficient authentication.”

The court rejected the argument that a signature consisting only of a first name has merely a “friendly” or informal character. Brokers may communicate in a casual manner, Lord Justice Tomlinson observed, but this does not diminish the gravity of the matters they conduct. Professionals understand perfectly well that their correspondence creates obligations binding their principals.

The case has significance extending beyond maritime law. It confirms that in English law what matters is not so much the wording or form of the signature as the intention to authenticate the document. This approach remains considerably more liberal than the position of the Polish Supreme Court, which consistently requires that a signature—however illegible—have a letter structure and constitute at least a distorted form of the signatory’s surname.

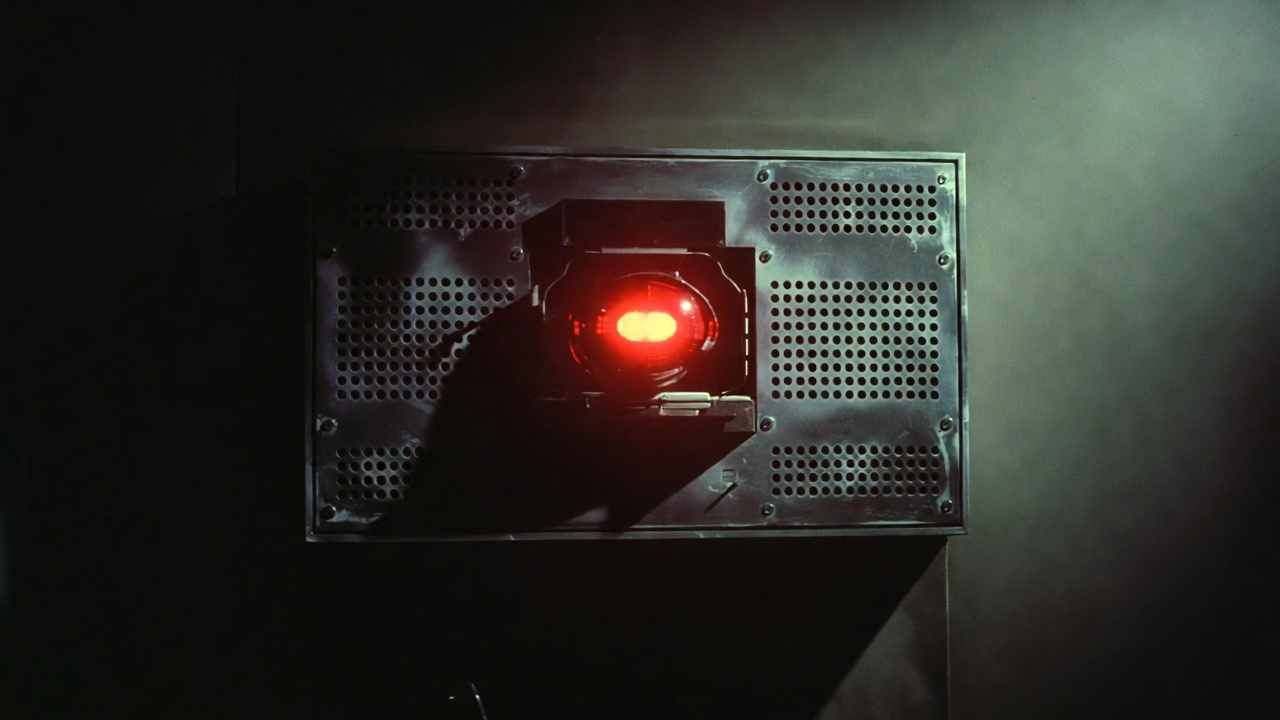

C. The United States: The Howland Will Forgery Trial (1868)—The Birth of Scientific Signature Analysis

The case of Hetty Green (née Robinson) against the executor of her aunt Sylvia Ann Howland’s estate represents a milestone in the history of forensic science. Hetty presented an earlier will leaving her the entire estate (approximately $2 million—a fortune at the time), with an attached card purporting to invalidate all subsequent wills.

The estate’s executor challenged the authenticity of the signature on the disputed card. The mathematician Charles Sanders Peirce and his father Benjamin Peirce were engaged to conduct a pioneering statistical analysis.

Charles Peirce compared 42 examples of Sylvia Howland’s signature, superimposing them and counting overlapping strokes. His father demonstrated that the distribution of overlapping elements in authentic signatures followed a binomial distribution—but the signatures on the disputed card overlapped in a manner statistically impossible for naturally executed signatures.

The Peirces’ analysis showed that the probability of such identical signatures arising naturally was approximately 1 in 2.666 quintillion. Although this evidence was scientifically impressive and pioneering, the court ultimately dismissed the case on procedural grounds—Hetty Robinson’s testimony as the sole witness and simultaneous beneficiary was deemed inadmissible under then-applicable law (equivalent to the “dead man’s statute”). The case was settled for approximately $600,000.

The significance of this case lies in its establishment of a precedent for the use of statistical analysis in judicial proceedings and its contribution to the principle that a natural signature is never identical—a certain variability is characteristic of authenticity, while excessive repeatability may indicate forgery. This insight forms the foundation of modern questioned document examination.

IV. Polish Jurisprudence on Signature Validity

A. The Minimum Content Requirement

On the question of minimum signature content, Polish jurisprudence takes a clear position: a signature must include at least the surname. This position, established during the interwar period, was confirmed in the cited 1993 Supreme Court resolution and has been consistently maintained in subsequent decisions.

In its judgment of March 8, 2012 (III CSK 209/11), the Supreme Court categorically stated: “a signature cannot consist of arbitrary graphic marks, but must comprise letters forming, in principle, the name and surname of the person who signs.”

This requirement is absolute with respect to acts requiring written form under penalty of nullity. As the Supreme Court explained in its order of June 17, 2009 (IV CSK 78/09): “In principle, a signature should express at least the surname. It is not necessary that the surname appear in full, as abbreviation is permissible.”

B. Signatures on Testaments in Letter Form

An interesting exception applies to holographic wills executed in letter form. In a resolution of April 28, 1973, the Supreme Court permitted signing of a will in a manner indicating only the testator’s family relationship to the beneficiary (e.g., “Your mother”), provided circumstances raise no doubt as to the seriousness and intent of such disposition.

This liberal standard derives from the principle of favor testamenti—the favorable interpretation of testamentary formalities. In 1993, however, the Supreme Court expressly cautioned that “these more lenient requirements, developed in case law regarding testaments executed in letter form, cannot be extended to all legal acts, especially to acts specified in the Law on Bills of Exchange, which constitutes ius strictum.”

C. Pseudonyms as Signatures

An interesting question was resolved by the Supreme Court in its judgment of October 23, 2020 (III CSK 134/18), concerning the distinction between pseudonym and nickname. The Court held that a pseudonym may substitute for a surname if the testator “in daily life and legal relations used the pseudonym.”

The condition, however, is that the pseudonym fulfill an identificatory function equivalent to the surname—that is, that it actually replace name and surname in transactions, rather than merely supplement them (as a nickname does). The Court explained: “A pseudonym fulfills an individualizing function, replacing name and surname, performing the same role. . . . A nickname, by contrast, does not signify anonymity with respect to the proper name and surname.”

D. From Bills of Exchange to Wills and Criminal Procedure: Evolution of the Standard

The seven-judge resolution III CZP 146/93 became the starting point for broader judicial reflection on the concept of signature. Particularly significant is the Civil Chamber’s order of June 17, 2009 (IV CSK 78/09), which transferred the bill-of-exchange standard to inheritance law and was subsequently adopted by the Criminal Chamber.

1. Order IV CSK 78/09—Civil Synthesis

The case concerned a notarial will executed by a person whose ability to write was in doubt. The Supreme Court, vacating the challenged order, formulated a synthetic statement of signature requirements that became the reference point for subsequent jurisprudence:

“In the absence of a statutory definition of signature, determination of the characteristics that a graphic mark must possess to be recognized as a signature is the subject of judicial and doctrinal commentary. Despite divergent views, a certain common minimum can be identified regarding these characteristics. In principle, a signature should express at least the surname. It is not necessary that the surname appear in full, as abbreviation is permissible; nor need it be fully legible. A signature should, however, consist of letters and enable identification of its author, as well as permit comparison and determination whether it was made in the form customarily used by that person; a signature should therefore exhibit individual and repeatable characteristics.”

Significantly, the Court expressly referred to resolution III CZP 146/93, noting that although “the resolution concerned the signature of a bill-of-exchange issuer, it has broader significance.” At the same time, the Court explained the relationship between the concept of signature and the ability to write: “In jurisprudence and legal scholarship, the position is widely accepted . . . that a signature can be made only by a person who knows how to and is able to write.”

The Court also emphasized the functional aspect of signature: “A signature is associated, inter alia, with the authenticity of the document and the conformity of its content with the will of the signing person, since a signature fulfills an identificatory function while simultaneously constituting ‘approval’ of the document.”

2. Minimum Requirements for Signature Validity

Particularly valuable is the Supreme Court’s indication regarding the limits of interpretive liberalism:

“Even under the most lenient treatment of the criteria for recognizing a particular written mark as a signature, motivated by the character of the act (a declaration of last will made before a notary), one cannot depart from the minimum requirement that the written mark enable identification of the person from whom it originates, at least according to such criteria as individual and repeatable characteristics.”

3. Signature Validity Criteria in Criminal Chamber Decisions

Order IV CSK 78/09 was expressly adopted by the Criminal Chamber in its order of September 22, 2011 (IV KK 222/11). In that case, the defense argued that beneath the District Court’s judgment “there is no linguistic or graphic sign indicating the identity of the person who issued the judgment.”

The Supreme Court, dismissing the cassation appeal, quoted extensively from IV CSK 78/09 and added:

“In principle, a signature should express at least the surname. It is not necessary that the surname appear in full, as abbreviation is permissible; nor need it be fully legible. A signature should, however, consist of letters and enable identification of its author, as well as permit comparison and determination whether it was made in the form customarily used by that person; a signature should therefore exhibit individual and repeatable characteristics. . . . Although a signature need not be legible, it should reflect characteristics specific to the person who makes it and thereby—indicate that person.”

The Criminal Chamber cited both order IV CSK 78/09 and resolution III CZP 146/93, confirming the universality of the developed standard. Also invoked was the judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of May 14, 2009 (II GSK 964/08), in which it was stated that “signing in an illegible manner, yet one typical and characteristic of a given person, sufficiently individualizes the signatory. Contrary therefore to the position expressed in the cassation appeal, failure to sign legibly cannot alone mean that the function of identifying the person making the declaration of will has been violated.”

4. Order II KK 328/22—Apparent Liberalization

A later order of September 26, 2022 (II KK 328/22) contains language that might raise doubts: “Marks distinguished beneath the judgment, even if they do not exist in linguistic or graphic form and do not precisely indicate the identity of the person issuing the judgment, are signatures within the meaning of Article 113 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.”

Read in isolation, this formulation might suggest abandonment of the letter-structure requirement. Such interpretation would, however, be erroneous. First, order II KK 328/22 itself invokes the standard from IV KK 222/11, requiring individual and repeatable characteristics. Second, the Supreme Court expressly noted that resolution III CZP 146/93 “regulates signature questions in the context of bills-of-exchange law and thus concerns an entirely different category of documents”—which paradoxically confirms that the civil standard remains the reference point.

5. The Specificity of the Criminal Procedure Context

The Criminal Chamber’s liberal approach finds justification in the identificatory mechanisms proper to criminal procedure. As the Supreme Court indicated: “The name and surname of the signing judge always appears from the comparison of that decision, since designation of the judge (judges) is a mandatory element of the judgment (Article 413 § 1 item 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure).”

The judge’s signature thus serves primarily an authenticating function—it confirms that the decision was issued with the knowledge and will of the signatories and that its content corresponds to the result of deliberation and voting. The identificatory function is fulfilled by the judgment’s preamble, not by the signature itself.

In specific cases, the Supreme Court examined whether the signature on a judgment matched signatures on other documents in the case file (orders, protocols), which enabled verification of authenticity despite illegibility.

E. Synthesis: Common Standard, Differentiated Contexts

Analysis of the jurisprudential line from III CZP 146/93 through IV CSK 78/09 to IV KK 222/11 and II KK 328/22 reveals fundamental consistency with contextual differentiation:

| Requirement | Bills of Exchange | Inheritance Law | Criminal Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surname (even abbreviated) | YES | YES | YES* |

| Letter structure | YES | YES | YES* |

| Legibility | NO | NO | NO |

| Individual and repeatable characteristics | YES | YES | YES |

| Customarily used form | YES | YES | YES |

*In criminal procedure, these requirements are verified together with the judgment preamble, which mitigates their practical significance.

For practitioners operating across different legal orders, the essential understanding is that the minimum remains common: a graphic mark must exhibit individual and repeatable characteristics enabling identification of the person through comparison with his other signatures. Differences concern only whether the signature must independently fulfill the identificatory function (bills of exchange) or may be supported by other elements of the document (judgment preamble, notarial act context).

V. Paraph and Initials: The Line That Must Not Be Crossed

A. The Clear Distinction

While an illegible signature may be valid, a mere paraph or initials do not constitute a signature within the meaning of provisions requiring written form. This distinction is of fundamental importance and has been unequivocally confirmed in Polish jurisprudence.

The Supreme Court in its 1993 resolution explained the difference: “One must distinguish the concept of paraph from abbreviated signature. The former—in the strict sense regarding form—means a manual mark consisting of initials; the latter—an abbreviated signature through omission of certain letters to make it shorter.”

B. The Function of the Paraph: Initialing, Not Signing

The functional difference is crucial. A paraph “constitutes a means of initialing a document, intended to indicate that it is prepared for signature.” Even when the initialing party places a full signature on the document but in the space designated for a paraph, “his mark retains the significance of preparing the document for signature.”

For this reason, the Supreme Court categorically stated: “Such certainty [that the signatory intended to sign with his full surname] is not created by initials alone, i.e., a paraph, and therefore they cannot be recognized as a signature.”

C. Contrast with English Law

The Polish position is notably more rigorous than the Anglo-American approach. In Golden Ocean, the Court of Appeal accepted signatures in the form of a first name alone or initials. In Poland, such an approach would be impermissible for acts requiring written form.

This difference stems from divergent philosophies: English law focuses on the signatory’s intention; Polish law—on the objective recognizability of the signature as a surname.

VI. Is an Illegible Signature More Difficult to Forge?

The structural complexity of a signature, measured by the number of direction changes (turning points), line intersections, and length, constitutes the primary determinant of forgery difficulty. Signatures containing many direction changes and line intersections—regardless of whether they are legible—require significantly greater effort from potential forgers than simple signatures.

Research has demonstrated that forensic document examiners achieve 95% specificity (ability to correctly reject forgeries) for signatures of medium complexity, but only 73% for signatures of low complexity, where their performance approaches that of untrained persons. The real concern, therefore, is not the signature’s legibility itself, but rather its actual structural complexity.

The Lesson from the Howland Case

The Howland case of 1868 taught the legal world something paradoxical: an excessively perfect signature arouses suspicion. Authentic signatures of the same person are never identical—natural motor variability ensures that each signature differs slightly.

Forgers, particularly those using tracing techniques, produce signatures too similar to the exemplar. It was precisely this excessive conformity that betrayed the forgery in the Howland case and remains one of the primary indicators used by contemporary experts.

VII. Synthesis of Signature Validity Standards

A. Common Denominators

Despite differences among legal systems, one can identify elements recognized globally:

- The intention to authenticate is more important than graphic form

- Consistency—a signature should be made in a repeatable manner

- Context—requirements may differ for different types of documents

- Functionality—a signature must enable identification of the signatory

B. The Polish Position

Polish jurisprudence occupies an intermediate position between German rigorism and Anglo-American liberalism:

- It does not require legibility (like English law)

- But requires letter structure and connection to the surname (like German law)

- It rejects paraphs and initials (unlike some English decisions)

- It permits certain flexibility for wills (the favor testamenti principle)

VIII. Practical Conclusions

For Document Signatories:

- Develop a characteristic, repeatable signature

- Ensure it contains recognizable elements of your surname

- A paraph may supplement but cannot replace a signature

For Legal Practitioners:

- Do not challenge a signature merely because it is illegible

- Verify whether the signature has letter structure

- Compare with other signatures of the same person

- In cross-border transactions, account for jurisdictional differences

For Business Professionals:

- Consider printing the surname beneath the signature line

- For documents of significant importance—witnesses or notarization

- For electronic signatures—select security levels adequate to the risk

This article is informational in nature and does not constitute legal advice. For specific matters, consultation with legal counsel is recommended.

Robert Nogacki – licensed legal counsel (radca prawny, WA-9026), Founder of Kancelaria Prawna Skarbiec.

There are lawyers who practice law. And there are those who deal with problems for which the law has no ready answer. For over twenty years, Kancelaria Skarbiec has worked at the intersection of tax law, corporate structures, and the deeply human reluctance to give the state more than the state is owed. We advise entrepreneurs from over a dozen countries – from those on the Forbes list to those whose bank account was just seized by the tax authority and who do not know what to do tomorrow morning.

One of the most frequently cited experts on tax law in Polish media – he writes for Rzeczpospolita, Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, and Parkiet not because it looks good on a résumé, but because certain things cannot be explained in a court filing and someone needs to say them out loud. Author of AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto: Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator. Co-author of the award-winning book Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy (Security of a Modern Company).

Kancelaria Skarbiec holds top positions in the tax law firm rankings of Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Four-time winner of the European Medal, recipient of the title International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.

He specializes in tax disputes with fiscal authorities, international tax planning, crypto-asset regulation, and asset protection. Since 2006, he has led the WGI case – one of the longest-running criminal proceedings in the history of the Polish financial market – because there are things you do not leave half-done, even if they take two decades. He believes the law is too serious to be treated only seriously – and that the best legal advice is the kind that ensures the client never has to stand before a court.