The Boomerang: How Instruments of Repression Turn on Their Makers

Tools forged to fight “enemies of the system” rarely remain in the hands of those who crafted them. Criminal law—especially in its harshest forms, including measures deployed before conviction—resembles a double-edged sword. Depending on who wields it, the blade can serve either to protect the legal order or to exact political revenge.

When we observe today how bank accounts are frozen, forced mortgages imposed on real estate, and passports cancelled for people who, just a few years ago, ran the justice system themselves, it’s hard to resist a reflection that reaches beyond immediate political commentary—the sort I’d prefer to avoid. The architects of repressive systems not infrequently become their victims. The twentieth century supplies countless examples. In recent years, Poland’s legislature has created an arsenal of procedural coercion instruments of unprecedented force: extended confiscation with a reversed burden of proof, enterprise forfeiture, the ability to secure assets based on mere suspicion, presumptions covering all property acquired in the five years before an alleged crime.

These legal instruments of extraordinary force, designed as weapons in the fight against organized crime and corruption, introduced “to prevent profiting from illegally obtained assets”—are now turning against their creators.

This dynamic—which might be called the “boomerang effect” of repressive instruments—leads us to two fundamental questions about the nature of power. First, do systems based on expansive procedural coercion display a structural tendency to place people least morally suited for the job in key positions? Second, does power—particularly criminal power equipped with tools that intrude on basic individual rights—ever voluntarily relinquish them?

Friedrich Hayek, analyzing the dynamics of totalitarian systems in The Road to Serfdom, and Ludwig von Mises, examining the spiral of interventionism, offer analytical frameworks for understanding these phenomena. Their theses, formulated in the mid-twentieth century, retain an unsettling relevance to contemporary dilemmas of criminal procedure.

I. The Danger of “Zero Tolerance” and “Tougher Sanctions”: Discretionary Power as Temptation

Extended Confiscation: Inverting the Presumption of Innocence

Introduced by an act of March 23, 2017, extended confiscation (Article 45 § 2-3 of the Criminal Code) represents the most controversial element of this arsenal. Its essence is a radical transfer of the burden of proof: not the prosecutor but the accused must prove the legality of his assets. The presumption covers everything the perpetrator acquired in the five years before committing the crime up until the issuance of a verdict—even one that’s not yet final.

The scope of the presumption is extraordinarily broad. As the commentary to the Criminal Code notes: “The presumption concerns not only property that the perpetrator took into possession but also property to which he obtained any title. Thus, forfeiture may cover property not owned by the perpetrator.” What’s more, the provision extends to third parties—if property has been transferred to family, friends, or other entities, they too can lose it, unless they prove that “based on circumstances attending the acquisition, one could not have suspected that the property, even indirectly, originated from a prohibited act.”

Asset Securing: Sanctions Before Verdict

Extended confiscation isn’t the only tool. Asset securing (Article 291 of the Code of Criminal Procedure) allows the seizure of an accused person’s property during the preliminary proceedings—by decision of the authorities, if only “there is justified fear that without such securing, execution of the judgment will be impossible or significantly impeded.”

In practice, this means that a person whose charges haven’t yet been proven can be deprived of access to financial resources, a business, or real estate.

Three Fundamental Threats

These mechanisms carry three essential dangers.

First, they invert the logic of the presumption of innocence. In a democratic state governed by the rule of law, the burden of proof rests with the prosecutor. Extended confiscation turns this principle on its head: the accused must prove he didn’t commit a crime from which his assets might have originated. This construction places the individual in a position where he must prove negative facts—prove he didn’t commit a crime.

Second, they create opportunities for abuse through their discretionary nature. Decisions about securing assets are made in the early stage of proceedings, often based on incomplete evidence, under conditions of media and political pressure. Authorities possess broad discretion—”justified fear” suffices. This vagueness becomes the gate through which arbitrariness enters.

Third, the consequences are practically irreversible, though theoretically temporary. The reputational consequences of asset seizure alone are permanent. The procedural instrument becomes a de facto punishment before the court has issued a verdict.

The key question, however—one Hayek made central to his analysis—is that repression mechanisms always operate in the context of human decision. Every decision is subject to distortions arising both from the character of those making it and from the institutional structure in which they operate. The question, then, is: what type of personality will gravitate toward positions where one exercises power over the lives and property of others in a regime where coercive means are broad and oversight limited?

II. “Why the Worst Get on Top”: Hayek’s Mechanism of Negative Selection

Hayek devoted the tenth chapter of The Road to Serfdom to unraveling a key paradox of totalitarianisms: why did systems proclaiming service to the community and built in the name of high ideals end up under the rule of ruthless, cruel people who scorned all morality?

The answer extends beyond the simple conclusion that “power corrupts“—though that, too, remains true. Hayek identified a structural selection mechanism that in systems based on centralized power systematically rewards certain character traits. And these aren’t necessarily socially desirable traits.

Three Principles of Negative Selection

Principle One: Uniformity Requires Intellectual Simplicity

Hayek begins with a fundamental sociological observation: the higher the level of education and intellect, the greater the diversity of views and value hierarchies. People with developed tastes, complex worldviews, moral sensitivity—rarely agree on details.

If, however, we’re building a system requiring unanimity on fundamental goals—like a justice system subordinated to a single center of power—we must descend to a level where such unanimity is possible:

“In the first instance, it is probably true that in general the higher the education and intelligence of individuals becomes, the more their views and tastes are differentiated and the less likely they are to agree on a particular hierarchy of values. It is a corollary of this that if we wish to find a high degree of uniformity and similarity of outlook, we have to descend to the regions of lower moral and intellectual standards where the more primitive and ‘common’ instincts and tastes prevail.”

Hayek doesn’t claim that most people have low moral standards. He merely argues that the largest group of people with very similar values is found among those with simplified values—it’s the “lowest common denominator.” If we need a strong, disciplined structure capable of imposing its will—like an authority equipped with extended confiscation instruments—this group becomes a natural reservoir of personnel.

Principle Two: Propaganda Attracts Susceptible Minds

A group with similar, primitive convictions may be too small to effectively exercise power. Its ranks need expanding. Here enters propaganda and manipulation:

“He will be able to obtain the support of all the docile and gullible, who have no strong convictions of their own but are prepared to accept a ready-made system of values if it is only drummed into their ears sufficiently loudly and frequently.”

The totalitarian system grows by attracting those who lack deeply rooted convictions of their own but easily adopt a ready-made system when it’s repeated loudly enough. These are people whose “vague and imperfectly formed ideas are easily swayed and whose passions and emotions are readily aroused.”

In the context of the justice system, this means that people without deeper reflection on the limits of criminal power, on the presumption of innocence, on proportionality—will more easily accept orders “from above,” even if those orders violate basic principles of the rule of law.

Principle Three: Negative Programs Unite More Effectively Than Positive Ones

Hayek identifies a third—perhaps most important—mechanism:

“It seems to be almost a law of human nature that it is easier for people to agree on a negative program, on the hatred of an enemy, on the envy of the better off, than on any positive task.”

Building a criminal apparatus around a common enemy is infinitely easier than around a positive vision of justice requiring detailed arrangements. The enemy—whether it’s “organized crime,” “VAT mafias,” “tax fraudsters,” or “corruptionists”—becomes the system’s binding agent.

“The enemy, whether he be internal like the ‘Jew’ or the ‘Kulak’, or external, seems to be an indispensable requisite in the armoury of a totalitarian leader.”

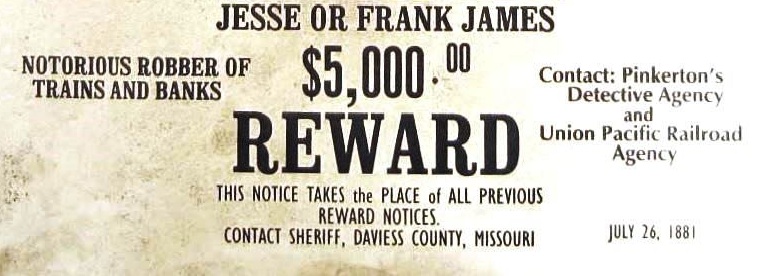

In the Polish context of 2016-2023, this enemy became “economic crime.” The rhetoric of “zero tolerance,” “fighting economic pathologies,” “recovering assets for the State Treasury”—these are classic examples of a negative program that doesn’t require a precise vision of justice, only the identification of an enemy and methods for fighting him.

Consequences for Power Structure: The Worst Rise to the Top

From these three principles emerges a dark conclusion: a system requiring centralized power and uniformity of goals inevitably rewards people with simplified worldviews, susceptible to manipulation, and capable of uncritically executing orders.

At the apex of such a system, we won’t find people who are intellectually outstanding, morally sensitive, or inclined toward compromise—these traits are dysfunctional in the logic of centralized criminal power. Instead, those who rise to the top will be people who:

- Have no deeply rooted moral convictions of their own that might conflict with superiors’ decisions or the “common good” as defined by the center of power.

- Are completely loyal to the leader and ready to execute any order regarding confiscation, asset securing, or other repression—regardless of its legal or moral dubiousness.

- Have a “taste for power itself”—pleasure in the ability to seize someone’s property, cancel a passport, deprive them of means of subsistence.

Hayek writes:

“There is thus in the positions of power little to attract those who hold moral beliefs of the kind which in the past have guided the European peoples, little which could compensate for the distastefulness of many of the particular tasks, and little opportunity to gratify any more idealistic desires, to recompense for the undeniable risk, the sacrifice of most of the pleasures of private life and of personal independence which the posts of great responsibility involve.”

Positions in the repression system—authorities equipped with extended confiscation, services seizing assets, offices cancelling passports—aren’t places for people with humanitarian feelings. Yet it’s precisely through these positions that the path to the very top of the system runs.

“Yet while there is little that is likely to induce men who are good by our standards to aspire to leading positions in the totalitarian machine, and much to deter them, there will be special opportunities for the ruthless and unscrupulous.”

Ruthlessness becomes a career path. The willingness to perform tasks we ourselves consider morally dubious but which are “necessary for a higher purpose”—fighting crime, protecting State Treasury interests—is the key to advancement.

Collective Ethics Replaces Individual Ethics

Hayek notes a paradox: the masses supporting systems of expanded repression aren’t at all lacking in moral fervor—quite the contrary:

“It would, however, be highly unjust to regard the masses of the totalitarian people as devoid of moral fervor because they give unstinted support to a system which to us seems a denial of most moral values. For the great majority of them the opposite is probably true: the intensity of the moral emotions behind a movement like that of National-Socialism or communism can probably be compared only to those of the great religious movements of history.”

People genuinely believe they’re serving the good—fighting crime, protecting State Treasury interests, building justice. The problem is that this “good” has been defined collectively, and the individual is merely a means to community ends.

Once we accept this premise—that an economic criminal is an enemy whose entire assets should be seized, even if their criminal origin hasn’t been proven—then “intolerance and brutal suppression of dissent, complete disregard for the life and happiness of the individual, are essential and unavoidable consequences of this basic premise.”

In the collective ethics that dominates systems based on expanded repression, the end justifies the means. There’s no act so wicked it can’t be justified by the “higher good” of fighting crime or protecting the public interest.

Hayek concludes:

“The principle that the end justifies the means is in individualist ethics regarded as the denial of all morals. In collectivist ethics it becomes necessarily the supreme rule.”

III. The Ratchet Effect: Power Never Retreats Voluntarily

The second pillar of Austrian-libertarian analysis concerns the temporal dynamics of state expansion. Hayek and Mises independently concluded that the state, once it assumes competences—particularly repressive competences—almost never voluntarily relinquishes them.

This mechanism, later formalized by Robert Higgs as the ratchet effect, explains why the scope of public authority—and especially criminal authority—tends toward one-directional growth.

The Logic of Interventionism According to Mises: The Spiral Never Retreats

Ludwig von Mises in A Critique of Interventionism (1929) and Human Action (1949) developed the theory of the “spiral of interventionism.” His thesis: every state intervention in the market (or more broadly, in the sphere of civil liberties) inevitably triggers unintended consequences that become justification for further interventions.

Mises’s classic example: price controls. When the state imposes a maximum price on a good below the market price, some producers will find production unprofitable and exit the market. Supply falls, shortages appear. The state responds with another intervention—it now controls not just prices but also factors of production, forcing producers to operate. This in turn requires control of raw materials, credit, labor… The spiral accelerates.

There is no other choice: either the government abstains from limited interference with the forces of the market, or it assumes total control over production and distribution. Either capitalism or socialism; there exists no middle way.

Interventionism—an attempt to create a “third way”—is, in Mises’s view, inherently unstable. It either collapses (through chaos) or transforms into full control. And at every stage of this spiral, the state doesn’t retreat from intervention but deepens it.

The reason is political: withdrawing intervention would mean admitting error, which carries high political costs. It’s much easier to double down and introduce another intervention, blaming the failure on “insufficient means” or “enemy sabotage.”

Translation to Criminal Law: The Spiral of Repression

Mises’s logic perfectly explains the development of criminal-procedural instruments in Poland after 2016:

Step 1: Harsher penalties were introduced for economic crimes—”invoice crimes” punishable by twenty-five years in prison, grand corruption with higher penalty thresholds.

Step 2: It turned out perpetrators were hiding assets. So extended confiscation was introduced with a presumption of criminal origin for all assets acquired over five years.

Step 3: It turned out perpetrators were transferring assets to third parties. So confiscation was extended to third parties with a presumption that everything they possess belongs to the perpetrator.

Step 4: It turned out that during proceedings perpetrators could dispose of assets. So asset securing was introduced already at the investigation stage, without judicial oversight.

Step 5: It turned out that escape needed to be prevented even more effectively. We cancel passports. Criminals won’t escape abroad.

Each step seemed “necessary” and “justified” in fighting crime. Each successive step was a consequence of the “insufficient effectiveness” of the previous one. The spiral never retreats—it only accelerates.

Hayek on “The Road to Serfdom”: The Ratchet Effect in Crises

Hayek developed a complementary analysis in The Road to Serfdom. While Mises focused on the economic logic of intervention, Hayek emphasized the political and psychological dynamics that fuel the accumulation of state power.

Hayek’s key thesis: power expands by leaps during crises but never retreats to pre-crisis levels. This is precisely the “ratchet effect”:

“Once government has embarked upon planning for the sake of justice, it cannot refuse responsibility for anybody’s fate or position.”

A government that takes responsibility for fighting economic crime creates expectations that it will fight it effectively. This forces it to continuously expand its powers to meet those expectations.

Hayek was particularly interested in how this dynamic works during extraordinary situations. He observed that measures introduced as “temporary” and “extraordinary” tend to become permanent elements of the legal system. The British experience during and after World War II—when wartime controls transformed into peacetime socialism—provided him with a powerful empirical example.

Contemporary Examples: From the USA PATRIOT Act to Extended Confiscation

The mechanism described by Hayek and Mises is confirmed in numerous contemporary examples.

The USA PATRIOT Act—passed as an emergency response to the September 11, 2001, attacks—was meant to be temporary. Twenty-four years later, its main provisions remain in force. As one analysis notes: “Emergency measures can calcify… when ongoing fear of terrorism freezes exceptions to civil liberties into standard practice, long after the initial crisis has passed.”

The 2008 financial crisis triggered a wave of new financial regulations and expanded state oversight. These regulatory frameworks “proved remarkably durable, constraining economic growth and innovation”—and no one seriously considers eliminating them.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought lockdowns, restrictions on movement, mask mandates, vaccine requirements. Though the end of the pandemic has been declared, many powers remain in the state’s arsenal, ready for reactivation at the next crisis.

Extended confiscation in Poland—introduced as a tool for fighting VAT mafias and organized crime—has been expanded over time. Initially it covered strictly economic crimes with specified benefit thresholds. Successive amendments expanded the catalog of crimes, lowered thresholds, broadened presumptions.

The retroactive force of confiscation provisions (Article 23 of the amending act of March 23, 2017)—clearly violating the prohibition on retroaction—was justified by the claim that perpetrators couldn’t be allowed to benefit from temporal loopholes. The exception became the rule.

Why Power Doesn’t Retreat: Four Barriers

The Hayek-Mises analysis points to four structural barriers preventing voluntary power retreat:

1. Political Barrier: Politicians who rolled back repressive measures would be accused of “supporting criminals” and “placing abstract human rights above citizen safety.” The political costs are too high.

2. Bureaucratic Barrier: As Hayek and Mises noted: “Bureaucracies and government agencies naturally grow in power and scope, because they seek to justify their existence by expanding their functions. Bureaucracies rarely, if ever, shrink.”

Authority equipped with extended confiscation has an interest in using it—this justifies budgets, positions, importance. No one voluntarily surrenders tools that increase their power.

3. Epistemological Barrier: When the state displaces market and social mechanisms, it destroys the knowledge needed to restore them.

An official accustomed to seizing assets based on “justified fear,” without detailed proof, won’t know how to operate in a system where every fact must be proven. Returning to pre-reform standards requires not only changing regulations but rebuilding an entire legal culture—which takes decades.

4. Ideological Barrier: Mises warned: “The prestige which this vain prophecy [of socialism’s inevitability] enjoys not only among Marxians, but among many who consider themselves as non-Marxian, is the principal instrument in socialism’s advance. It spreads defeatism among those who would otherwise stoutly resist the socialist menace.”

Similarly in criminal law: the ideology of “effectiveness at all costs,” the rhetoric of “zero tolerance,” the mantra “crime doesn’t pay”—create a climate where any attempt to roll back repressive measures is treated as a “soft approach to crime.”

Irreversibility as a Structural Feature

The Hayek-Mises analysis suggests that the irreversibility of state power expansion—particularly repressive power—isn’t accidental but structurally built into the logic of centralization.

Every intervention creates conditions—distortions, bureaucratic interests, ideological shifts, destroyed social knowledge—that make retreat increasingly difficult.

In the context of criminal procedural law, this means that every expansion of authorities’ powers, every new presumption, every lowering of evidentiary standards—becomes a point of no return.

Conclusion: Lessons for the Future

Observing today how instruments created to fight “enemies of the system” are being applied against their creators, we can draw three fundamental lessons.

Lesson One: Instruments of repression are amoral. A sword doesn’t ask whom it should behead. Extended confiscation, asset securing without conviction, presumptions of criminal asset origin—all these instruments work equally effectively (or destructively) regardless of whom they’re directed against. A politician who creates them, thinking he’ll control whom they strike, makes a cardinal error. Someday they may strike him.

Lesson Two: Centralized power attracts the wrong people. The “Why the Worst Get on Top” mechanism Hayek described isn’t a historical curiosity but a structural regularity. Systems based on extensive discretionary powers, on doctrinal uniformity, on loyalty to the center of power—will naturally select people with simplified worldviews, susceptible to manipulation, loyal to the leader, lacking deep moral convictions of their own.

This doesn’t mean all officials in the power system are bad. It means the system puts a premium on certain traits—and those who lack these traits will drop out earlier or resign themselves, because they won’t be able to function in such a structure.

Lesson Three: Power never retreats voluntarily. The ratchet effect described by Mises and Hayek isn’t theory—it’s an empirical regularity confirmed by hundreds of historical examples. A state that once gained specific repressive competences won’t surrender them voluntarily. It will expand them during successive crises, justifying this by the “insufficient effectiveness” of existing measures.

The only path to rolling back criminal power expansion leads through deep cultural and constitutional change—change that requires not only new regulations but a rebuilding of the entire legal culture, a restoration of trust in the presumption of innocence, a return of proportionality as the highest value of criminal law.

Without this change—successive governments, successive teams, successive “reformers” will reach for the same tools. And they’ll be surprised when one day those tools turn against them.

As Hayek warned in the conclusion of The Road to Serfdom: the problem lies not in who exercises power but in the scope of power available for exercise. As long as that scope encompasses confiscation without conviction, asset securing based on suspicion, presumption of guilt—we’ll live in a system where anyone can become a victim of mechanisms he himself helped create.

True reform requires not personnel change—it requires dismantling the machinery of repression itself.

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.