The Fortress and the Siege

How to Shield Your Business Within the Law

Every entrepreneur bears the risk of poor decisions, unreliable counterparties, or market shifts. That risk may lead to the summit—or cast one into the abyss, where even personal assets untouched by business operations come under threat. Understanding the relationship between asset security measures and asset protection allows one to build structures that withstand even the worst-case scenario.

A Map of Concepts: Four Distinct Legal Institutions

Before proceeding to specifics, we must distinguish institutions that are often confused in practice, though they belong to different branches of law and serve different purposes.

Asset Security (Public Law)

Asset security is a coercive measure applied by state authorities to guarantee execution of future judgments. It is temporary and preventive in nature—it does not satisfy the creditor but ensures that a future ruling can be enforced. It appears in three variants:

| Type | Legal Basis | Applying Authority |

|---|---|---|

| Security in criminal proceedings | Art. 291 CCP | Prosecutor, court |

| Security for tax liabilities | Art. 33 Tax Ordinance | Tax authority |

| Security in civil proceedings | Art. 730 et seq. CPC | Court upon creditor’s motion |

Enforcement (Compulsory Satisfaction)

Enforcement is a proceeding aimed at compulsory satisfaction of a creditor from the debtor’s assets. It occurs after an enforceable claim arises and requires an enforcement title. Unlike security—it leads to definitive deprivation of the debtor’s property. It may be conducted by a court bailiff or an administrative enforcement authority.

Actio Pauliana (Creditor Protection)

The actio Pauliana (Articles 527-534 of the Civil Code) is a civil law instrument protecting creditors against fraudulent asset transfers by debtors. It allows a legal act (e.g., gift, sale) to be declared ineffective against the creditor—even if the property formally belongs to another person.

Asset Protection (Entrepreneur’s Actions)

Asset protection is a set of lawful legal actions undertaken by an entrepreneur to safeguard assets against business risks—before any claim arises. It encompasses choice of legal form, corporate structures, family foundations, and asset diversification.

The Relationship Between These Institutions

The relationship between asset security and asset protection is one of attack and defense. But this is not the only connection:

ASSET PROTECTION (prevention)

↓

[time passes, claim arises]

↓

ACTIO PAULIANA (challenging transfers)

↓

ASSET SECURITY (freezing assets)

↓

ENFORCEMENT (compulsory satisfaction)

Key observation: The earlier on this timeline the entrepreneur acts, the greater the room for maneuver. The later—the less.

Time as a Critical Variable

Helmuth von Moltke maintained that errors committed during strategic deployment cannot be corrected in the course of the campaign. In the context of asset protection, this principle operates with full force:

| Moment | Situation | Scope for Action |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal | No threats on the horizon | Full freedom to build protective structures |

| Risky | Audits, proceedings, disputes underway | Actions may be challenged as fraudulent |

| Too late | Security order issued | Only appellate remedies remain |

| Definitively too late | Enforcement underway | Asset protection impossible; only procedural defense remains |

Actio Pauliana: The Boundary of Protective Actions

The actio Pauliana marks the boundary between lawful asset protection and acting to creditors’ detriment. If the debtor’s actions aim to prevent debt repayment, both the debtor and beneficiaries of dispositions made to creditors’ prejudice may be sued.

A Paulian judgment allows the creditor to satisfy his claim directly from the asset that was the subject of the challenged transaction—even if it formally belongs to another person.

When the Actio Pauliana Is Particularly Dangerous

The statute provides a presumption of acting to creditors’ prejudice in two situations:

- Gratuitous transaction (gift)—the creditor need not prove the donee’s bad faith

- Transaction with a close person—it is presumed the close person knew of the prejudice to creditors

In both cases, the burden of proof shifts to the debtor and beneficiary—they must demonstrate that no creditor was harmed.

Gifts: The Worst Possible Solution

A gift is a legal instrument that should be used only when:

- the donor, by diminishing his assets, does not render himself insolvent,

- he genuinely wishes to transfer the property gratuitously (it is not a sham transfer).

Sham donations will backfire faster than one might expect. The creditor has five years from the date of the transaction to bring an actio Pauliana—a long period of uncertainty.

Summary of Distinctions

| Institution | Branch of Law | Purpose | Who Applies | When |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset protection | Private law | Prevention | Entrepreneur | Before claims arise |

| Actio Pauliana | Civil law | Creditor protection | Creditor (court) | After fraudulent act |

| Asset security | Public/civil law | Guarantee of judgment execution | Authority/court | During proceedings |

| Enforcement | Enforcement law | Compulsory satisfaction | Bailiff/authority | After obtaining title |

Understanding these distinctions allows the entrepreneur to consciously plan asset protection—and to understand what “adversary” he faces at each stage.

The Absolute Boundary: Assets Derived from Crime

Regardless of how sophisticated the protective structures an entrepreneur builds, there exists a boundary that no legal construction can cross: no “asset protection” will work if the assets derive from criminal activity.

The provisions on extended confiscation (Article 45 § 2 of the Criminal Code) introduce a presumption that property acquired by the perpetrator within five years before commission of the offense constitutes proceeds of that offense—unless the perpetrator or another person demonstrates lawful origin. This presumption pierces all holding structures, foundations, and international transfers.

Article 44a of the Criminal Code goes further: upon conviction for an offense yielding substantial financial gain, the court may order forfeiture of an entire enterprise—if it served to commit the crime or conceal proceeds.

The conclusion is unequivocal: asset protection is an instrument for those who conduct business lawfully and wish to guard against business risks or overreach by authorities. It is not—and never will be—a tool for concealing the proceeds of crime. He who builds protective structures on foundations of illegal income builds on sand.

The Paradox of Ownership

The only fully effective way to protect personal assets is not to own them—while retaining control. This sounds paradoxical, but Polish law offers legitimate instruments to achieve precisely this result.

The Corporate Shield

Establishing a limited liability company or joint-stock company separates personal wealth from business assets. The entrepreneur’s liability, in principle, stops at the company’s door. But several caveats apply.

The tax dimension: Contributing non-cash assets other than an enterprise or its organized part generates taxable income. Cash contributions, or contributions of an entire business, do not.

The ownership dimension: Shares belong to the entrepreneur and can themselves be seized. Their attractiveness to creditors depends on careful drafting of the company’s articles of association—work that requires experienced counsel.

The Family Foundation

Since 2023, Polish entrepreneurs have access to a new vehicle: the family foundation, designed specifically for asset protection and succession planning. The founder divests himself of property without receiving shares in return, yet retains influence over management through the foundation’s charter.

Unlike traditional foundations, family foundations need not pursue publicly beneficial purposes. They may serve exclusively the interests of the founder and designated beneficiaries—and they enjoy favorable tax treatment.

The Murdoch family’s multi-decade struggle over their Nevada Asset Protection Trust offers a cautionary tale: even the most sophisticated legal architecture cannot substitute for family harmony. The best documents in the world cannot prevent litigation when siblings stop speaking.

The International Dimension

The second tier of protection involves structures beyond Polish borders. The instruments are similar—companies and foundations—but their character differs meaningfully.

Holding Companies

Depending on the assets to be protected, entrepreneurs deploy holding companies from various jurisdictions. These may serve as direct asset owners or as intermediate layers in ownership chains.

Private Foundations

Certain jurisdictions offer private foundations—entities created specifically to hold and manage personal wealth. Unlike Polish foundations, they need pursue no charitable purpose whatever. They exist solely to serve the founder’s interests. Assets transferred to such foundations can, without great difficulty, be returned to the founder or distributed to designated persons.

Geographic Diversification

Spreading assets across jurisdictions constitutes an element of protective strategy:

- Swiss bank accounts – traditional discretion, robust legal framework

- Liechtenstein accounts – private banking expertise

- Private banking in Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Dubai, Monaco – tailored wealth management

The Architecture of Defense

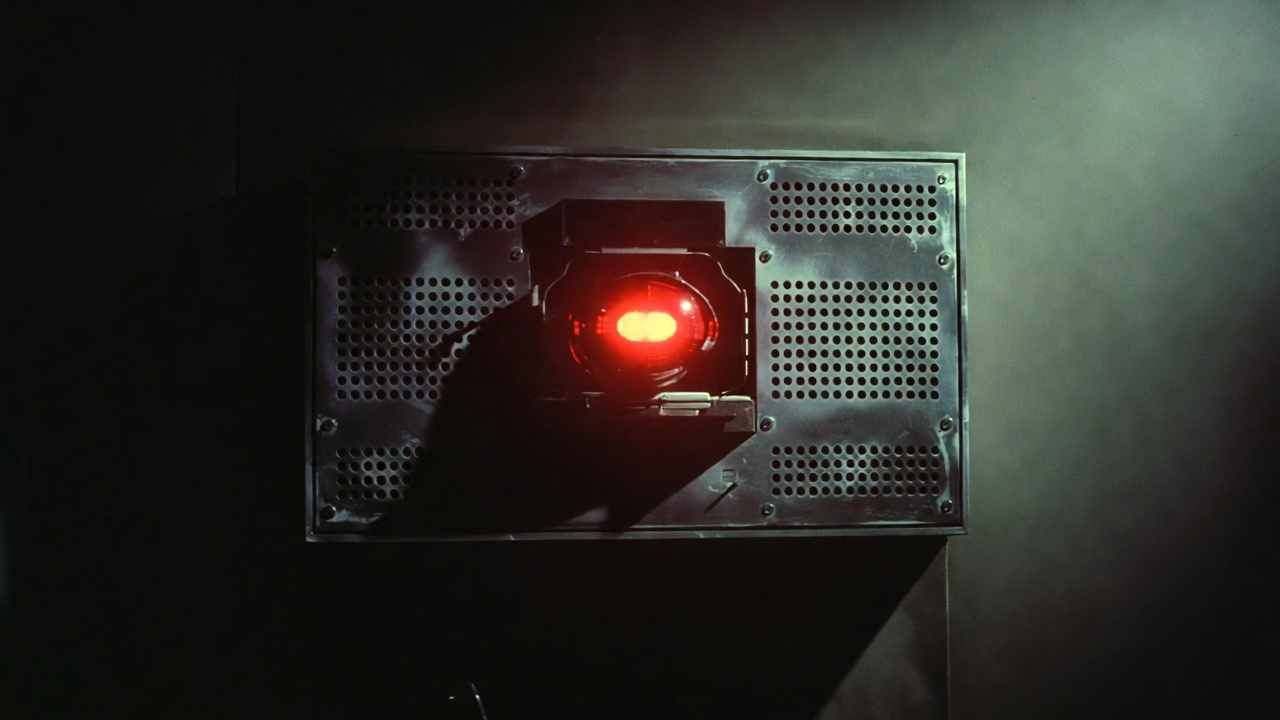

Sébastien de Vauban, Louis XIV’s military engineer, did not build single walls. He created fortification systems: moats, bastions, outworks, each conquered obstacle revealing another. Effective asset protection operates similarly.

| Layer | Function | Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| First | Separate business risk | Limited liability companies, corporate restructuring |

| Second | Protect family assets | Family foundations, investment policies |

| Third | Geographic diversification | International structures, foreign accounts |

| Fourth | Procedural defense | Legal remedies, court representation |

No single layer is impenetrable. Together, they create a system that dramatically raises the cost and difficulty of attack. And in the logic of conflict—as Liddell Hart taught—you win not by destroying your opponent, but by making continued combat unprofitable.

The Ethics of Defense

There exists a fundamental difference between protecting assets and hiding them from legitimate claims. The first is legal and ethically defensible. The second leads to criminal liability and reputational destruction.

Niccolò Machiavelli warned that a prince who relies solely on fortune falls when fortune changes. An entrepreneur who relies on the hope that problems will pass him by is playing roulette with fate. Asset protection means converting gambling into planning.

Conclusion

Sun Tzu wrote that the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting. In asset protection, this principle carries particular force. The best enforcement proceeding is one that cannot begin because there is nothing to seize. The best asset freeze is one that, even if applied, does not deprive the entrepreneur of everything.

Building such architecture requires acting before threats materialize, understanding the legal boundaries, and accepting that improvisation in this domain ends badly. The structures must exist before the siege begins. Once the army surrounds the walls, it is too late to dig the moat.

Related topics:

- Board member liability for company obligations

- Tax disputes and litigation

- Criminal tax and commercial matters

- Strategic legal advisory

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.