Frozen Russian Assets as a Vulture Fund Target

Tsarist Bonds, $225 Billion, and the New Lawfare Against Russia

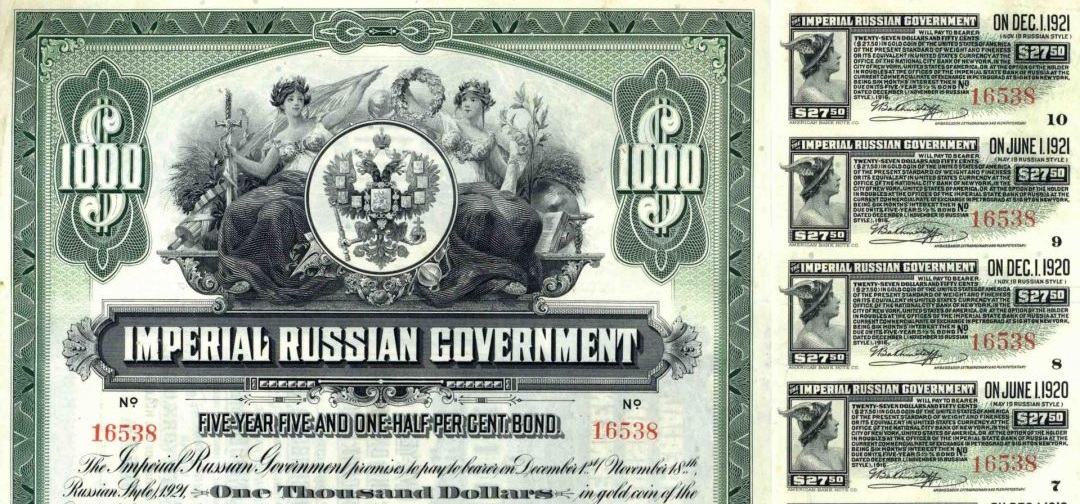

Twenty-five million dollars. This was the nominal value of the bonds that the Russian Empire sold to American investors through the National City Bank of New York in December 1916. The coupon rate stood at five and one-half percent per annum. The maturity: five years. The denomination: United States dollars, with a gold-clause provision permitting conversion at the prevailing gold parity.

Two hundred twenty-five billion, eight hundred million dollars. This figure—according to the complaint filed in June 2025—represents the present value of those same instruments, inclusive of accumulated interest calculated on a gold-adjusted basis. The multiplier: nine thousand and thirty-two.

Between these two figures lies a revolution that toppled a thousand-year dynasty. Two world wars. The rise and fall of the Soviet empire. The dissolution of the USSR. The invasion of Ukraine. And one fundamental question of law: Can an obligation incurred by a state that ceased to exist one hundred and ten years ago be enforced before a contemporary tribunal—and, more pressingly, can it unlock frozen Russian assets?

- See the LinkedIn post for discussion

Frozen Russian Assets: Three Hundred Billion Dollars in Legal Limbo

In response to Russia‘s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the United States and its allies froze Russian assets valued at approximately three hundred billion dollars. The bulk of these funds—reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, holdings of the National Wealth Fund, deposits of state financial institutions—sit in European and American financial institutions, inaccessible to Moscow yet untouchable by Western governments hesitant to take the unprecedented step of outright confiscation.

Into this stalemate steps an unexpected player: a vulture fund from Delaware, armed with century-old bonds and a sophisticated lawfare strategy.

Noble Capital: The Vulture Fund Whose Owners Remain in Shadow

Noble Capital RSD LLC is a limited-liability company registered in Delaware—the jurisdiction that, thanks to its permissive corporate law, has become home to most American legal entities, from tech giants to special-purpose vehicles. The initials “RSD” are no accident: they stand for Russian Sovereign Debt.

Who, exactly, are the people behind this vehicle? The question has no public answer—and the silence is itself revealing.

Delaware law does not require disclosure of LLC members or managers in publicly filed formation documents. The court docket identifies only counsel—Kenneth Noble of Noble Law PLLC, whose surname may or may not be coincidental—but not the beneficial owners. Corporate database searches turn up various entities with similar names (Noble Capital LLC, Noble Capital Group), none matching the profile of a fund specializing in Russian sovereign debt.

Vulture Funds: How They Profit from Sovereign Debt

Vulture funds—termed euphemistically “activist funds” or “specialized restructuring vehicles”—operate according to a strictly defined business model that differs fundamentally from traditional distressed-debt investing.

Stage One—Acquisition: Purchase sovereign debt on secondary markets at four to twenty cents per dollar of face value following default or during acute distress.

Stage Two—Holdout Strategy: Refuse to participate in multilateral restructuring negotiations, even when ninety percent or more of creditors accept terms. Traditional distressed investors participate in restructurings, accepting haircuts in exchange for the debtor’s return to solvency. Vulture funds do precisely the opposite.

Stage Three—Forum Shopping: Litigate in favorable jurisdictions—primarily New York and London, where most sovereign-bond documentation is governed.

Stage Four—Coercion Tactics: Seek injunctions blocking payments to restructured bondholders and pursue asset seizures in third countries—bank accounts, commercial receivables, even naval vessels.

Stage Five—Forced Settlement: Compel the sovereign debtor into settlement at multiples of purchase price through relentless legal and political pressure.

Documented returns range from three hundred to two thousand percent—numbers impossible in any conventional asset class.

The Argentina Case: Vulture Fund Paradigm

The paradigmatic example is the fifteen-year legal war waged by Paul Singer’s NML Capital—the billionaire whom The New Yorker called “the doomsday investor”—against Argentina.

Argentina defaulted in December 2001 on approximately one hundred billion dollars in obligations—the largest sovereign default in history at that time. In 2005 and 2010, the country conducted restructurings, achieving 93% creditor participation at roughly thirty cents on the dollar.

NML Capital refused to participate. The fund purchased Argentine bonds for an estimated $49 to $177 million, then waged a fifteen-year legal war that included:

- Obtaining a precedent-setting ruling interpreting the pari passu clause to prohibit payments to restructured bondholders unless holdouts were paid simultaneously in full

- Seizing the Argentine naval training vessel ARA Libertad in the Ghanaian port of Tema in October 2012—the ship, with three hundred sailors aboard, was detained for seventy-seven days

- Mounting a lobbying campaign in the U.S. Congress and funding think tanks portraying Argentina as a deadbeat debtor

The war ended in 2016 with a settlement of $2.4 billion—a return exceeding eleven hundred percent.

Singer’s triumph inspired a wave of imitators and ensured that every sovereign debtor must now factor vulture fund risk into its debt-management strategy.

Tsarist Bonds: What Did American Investors Actually Buy in 1916?

A Financial Instrument as Historical Artifact

The 1916 bonds are physical documents printed on security paper, embossed with the double-headed eagle of the Russian Empire, individually numbered, and equipped with interest coupons. They are bearer instruments—the holder is entitled to payment without demonstrating how possession was acquired. Transfer occurs through simple physical delivery. Specimens can still be purchased on the collectors’ market.

The Gold Clause: Source of Astronomical Claims

The crucial element was the gold clause. The document provided that payment would be made in U.S. dollars or Russian rubles at the holder’s option, with value converted according to the gold parity prevailing at issuance.

In 1916, an ounce of gold cost $20.67—a price set by the United States in 1834 and maintained for the next century. Today, the price hovers around two thousand dollars per ounce. This hundredfold increase in gold’s value, multiplied by one hundred and eight years of compound interest, generates the $225.8 billion figure.

Why Did Americans Buy Russian Bonds?

December 1916 marked the apex of World War I. The Russian Empire was an Entente ally, fighting alongside Britain and France against Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Eastern Front was consuming millions of soldiers and vast material resources. Russia desperately needed capital to finance the war effort.

For American investors, tsarist bonds appeared attractive. The interest rate significantly exceeded that offered by U.S. Treasury securities. Russia was a military and economic power with enormous natural resources. Alliance with Britain and France seemed to guarantee victory in the war.

No one anticipated that within three months Tsar Nicholas II would abdicate, and within a year the Bolsheviks would seize power and refuse to pay any debts of previous governments.

The 1918 Decree: Revolution as Legal Event

The text of the Decree on the Annulment of State Loans, signed by Yakov Sverdlov, is characterized by ruthless clarity:

“All state loans contracted by the governments of the Russian landowners and bourgeoisie are hereby annulled as of December 1917. The coupons of these loans falling due in December 1917 shall not be honored. Similarly annulled are the guarantees given by the above-named governments for the loans of various enterprises and institutions. All foreign loans, without exception, are unconditionally annulled.”

The decree extinguished approximately sixty billion rubles in obligations—sixteen billion in foreign debt. France, where an estimated 1.6 million citizens held Russian bonds, was hit particularly hard. The loss entered French collective memory under the name emprunts russes (Russian loans), becoming a byword for naïve faith in the solidity of foreign investment.

For the Bolsheviks, repudiation was not an act of financial desperation but a conscious ideological choice. Trotsky liked to point out that the Saint Petersburg Soviet of 1905 had warned Western bankers that loans to the Tsar would not be honored by a victorious revolution.

The Odious Debt Doctrine: When Is Sovereign Debt Invalid?

The Sack Paradox

The theoretical foundations for the legal legitimization of the Bolshevik repudiation were laid not by any Marxist but by a former official of the Tsar’s Finance Ministry. Alexander Nahum Sack, who emigrated after the revolution and settled in France, published a treatise in 1927 formulating the doctrine of dette odieuse—odious debt.

Sack formulated three conditions whose joint satisfaction allows debt to be classified as odious:

First, lack of consent. The debt was incurred without the population’s consent, by a government lacking democratic legitimacy. Tsarist autocracy, in which sovereign power was concentrated in the monarch’s person and the population had no influence over financial policy, satisfied this condition.

Second, lack of benefit. The loan proceeds were not used for the needs or interests of society. Military expansion, suppression of revolutionary movements, maintenance of the apparatus of repression—these were goals serving the rulers, not the people.

Third, creditor awareness. Lenders knew or should have known of the two preceding circumstances. Western banks were under no illusions about to whom they were lending money.

The 1916 tsarist bonds satisfied all three criteria.

The Vienna Convention on Succession of States of 1983—which never entered into force—recognizes the right of successor states to refuse assumption of debts contrary to fundamental principles of international law.

The British and French Settlements: Diplomacy, Not Legal Obligation

Noble Capital may argue that since Russia voluntarily satisfied British and French bondholders, it acknowledged its responsibility for tsarist debts. This argument is fundamentally flawed.

United Kingdom, 1986

In July 1986, the Soviet Union and United Kingdom reached an agreement that media portrayed as “repayment” of tsarist debt. In reality, the mechanism was different: the settlement released frozen tsarist assets held in British banks since 1917 and permitted their distribution to bondholders. The amount covered approximately two percent of claims. In exchange, the USSR gained access to London capital markets.

France, 1996

The Franco-Russian agreement of November 1996 provided for payment of four hundred million dollars—less than ten percent of the estimated value of French claims. In exchange, France waived further claims, and Russia gained membership in the Paris Club as a creditor nation.

Both settlements were voluntary political compromises—ex gratia gestures, not performance of legal obligations. A voluntary gift to one beggar does not create a legal obligation to give alms to all.

Anatomy of the Lawsuit: Frozen Russian Assets as the Real Target

The architecture of Noble Capital’s claims reveals the legal sophistication behind a seemingly quixotic demand.

Declaratory Judgment: Playing the Long Game

First, Noble Capital seeks a declaratory judgment establishing that Russia is indebted to the plaintiff in the amount of at least $225.8 billion. Unlike a money judgment, which orders the defendant to pay and can be enforced through asset seizure, a declaratory judgment merely authoritatively resolves the legal question.

Why would a plaintiff choose the seemingly weaker remedy? For three reasons:

- Circumventing execution immunity—even if a court recognized the claim, frozen Russian assets are protected from execution under FSIA. A declaratory judgment establishes the creditor’s rights without immediately confronting that barrier.

- Preparing ground for future action—a final judgment could serve as the basis for set-off in other transactions, enforcement actions in other jurisdictions, or settlement negotiations from a position of strength.

- Avoiding prematurity objections—demanding immediate payment from frozen assets would likely be dismissed as impossible under current law (OFAC sanctions block all transactions involving Russian state property).

Set-Off Rights: The Key to Frozen Assets

Second, the plaintiff seeks a declaration recognizing the right to set off tsarist-bond claims against any obligations that Noble Capital or its assignees might owe Russia—including obligations arising from frozen Russian assets.

This element is crucial for understanding the entire strategy. Noble Capital does not seek direct execution against frozen Russian assets but rather the right to use them as a compensatory instrument in the future, when the legal situation changes.

Equitable Receiver: A Trap Awaiting Unfreezing

Third, the plaintiff seeks appointment of an equitable receiver who would take control of Russian assets in the United States the moment they are unfrozen—before Russia could withdraw or conceal them.

This architecture reveals a long-term play. Noble Capital is not counting on immediate payment. It is betting that someday—a year from now, ten years, twenty—geopolitical circumstances will shift, sanctions will be lifted or modified, and frozen Russian assets will become accessible. At that moment, a final judgment from a United States federal court will transform from a piece of paper into a weapon of extraordinary leverage.

Sovereign Immunity: Can Russia Be Sued in U.S. Courts?

FSIA and the Commercial Activity Exception

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 codifies in American law the principle of sovereign immunity. Foreign states are not subject to the jurisdiction of U.S. courts—unless a claim falls within one of the enumerated exceptions.

Noble Capital relies on the commercial-activity exception in 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2). The provision excludes immunity when a suit is based on commercial activity conducted by the foreign state.

The key precedent is the Supreme Court’s decision in Republic of Argentina v. Weltover, Inc. (1992), which held that issuing “garden-variety debt instruments” constitutes commercial activity.

Why Tsarist Bonds Are Not “Garden-Variety Debt Instruments”

The analogy to Weltover is superficial, however:

- Argentine bonds were ordinary budget-deficit financing instruments, issued in peacetime by a democratically elected government. Tsarist bonds financed a war effort, issued by an autocratic regime on the brink of collapse.

- Argentina in the 1990s was the same state that incurred the debt. The Russian Federation is a distant legal successor, separated by three revolutions.

- Argentine bonds contained explicit choice-of-law and jurisdiction clauses. Tsarist bonds were issued in an era when the concept of sovereign immunity was absolute.

French courts consistently dismissed similar claims, holding that tsarist bonds were actes de souveraineté—acts inherently sovereign in character.

Central Bank Execution Immunity

Even if a court found jurisdiction, the frozen Russian assets of the Central Bank enjoy special protection. 28 U.S.C. § 1611(b)(1) provides that property of a foreign central bank held for its own account is immune from execution unless the bank has explicitly waived that immunity.

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation has made no such waiver.

Statute of Limitations: Can Claims Be Pursued After a Century?

The Time Problem

The tsarist bonds became due no later than 1921. More than one hundred years have passed since then. Even the most liberal calculation of limitation periods does not permit claims to be pursued after a century.

Noble Capital’s Argument: Force Majeure?

The plaintiff may attempt to invoke the doctrine of equitable tolling—suspension of the limitations period on grounds of equity. The argument would run as follows: limitations do not run against a creditor when the debtor actively denies that any obligation exists.

This argument is legally deficient for several reasons:

First, debt repudiation is not equivalent to the debtor “hiding.” It is the opposite—a public, notorious declaration refusing to perform the obligation. The 1918 decree was announced urbi et orbi.

Second, American courts were available to bondholders throughout this period. The absence of U.S. diplomatic recognition of the USSR (until 1933) did not close the courthouse doors.

Third, even if some period of “suspension” were conceded, it would have ended no later than the USSR’s dissolution in 1991. More than thirty years have passed since then.

The Chinese Analogy

Judge Amir Ali dismissed in September 2025 a Noble Capital LLC lawsuit against China seeking $11.5 billion on imperial bonds from 1898–1911, holding, among other things, that the claims were time-barred. If sixty-five years is too long for Chinese bonds, then one hundred four years certainly exceeds the limits of legal patience.

Lawfare: When Law Becomes a Weapon in Geopolitical Competition

What Is Lawfare?

The term lawfare—a blend of law and warfare—denotes the strategic use of legal rules, forums, and procedures as weapons to achieve political, military, or geopolitical objectives that would otherwise require traditional coercive means. Major General Charles Dunlap, who popularized the concept, defines lawfare as “using law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve an operational objective”.

Contemporary analyses distinguish between offensive lawfare (harassing, constraining, or delegitimizing an opponent) and defensive lawfare (building legal resilience and deterrence). Studies of Russian and Chinese strategy emphasize that “legal warfare” constitutes an integral element of hybrid warfare doctrine, alongside information and psychological operations.

Frozen Russian Assets as a Lawfare Battlefield

The debate over frozen Russian assets is a textbook example of lawfare, where both sides of the conflict deploy legal arguments, courts, and institutional procedures as instruments in a broader political and economic confrontation.

Western lawfare involves constructing legal frameworks enabling the use of frozen assets for Ukraine’s benefit. Key strategies include:

- Using profits (windfall income) from sovereign assets without touching the principal—the EU decision of May 2024 and subsequent G7 arrangements

- Designing a “reparations loan” mechanism where future profits from frozen reserves service debt raised for Ukraine

- Argumentation based on the doctrine of countermeasures against a flagrant breach of international law (aggression)

Russian lawfare constitutes a response contesting the legality of the freeze and threatening counter-measures:

- Moscow characterizes the freezing of sovereign reserves as illegal expropriation violating state immunity

- Russia threatens to seize Western investors’ assets on its territory, explicitly linking their value to the size of frozen reserves abroad

- It signals challenges in international and national courts

The Noble Capital Lawsuit in the Lawfare Context

The timing of Noble Capital’s lawsuit is suggestive. It was filed precisely as Western governments were intensively debating mobilization of frozen Russian assets for Ukraine’s reconstruction—and as the European Parliament conducted heated debates over mechanisms for their use. Any legal action complicating the status of these assets could serve as an instrument of pressure—or, conversely, as an obstacle to multilateral negotiations.

In the world of lawfare, such vehicles not infrequently serve purposes their true principals prefer not to disclose. Law becomes the battlefield for extracting or blocking economic value—each side uses legal institutions and narratives (reparations vs. theft, countermeasures vs. expropriation) to shape legitimacy, deter adversaries, and influence third-state and market behavior.

A Delaware LLC, represented by a law firm bearing the same surname as the entity, pursuing claims exceeding the annual budgets of most nation-states, in a matter touching the hottest geopolitical confrontation of our time: this is a configuration that should interest analysts well beyond the legal profession.

Are the backers veterans of the Argentina campaign? New players staking a speculative position? Or interests extending beyond pure financial return—perhaps intelligence services or state actors using the fund as a deniable platform for lawfare operations? Public sources offer no answers. Perhaps discovery proceedings or future disclosures will illuminate the ownership structure. Until then, the mystery remains an integral part of this story.

Comparative Context: Other Historical Debt Disputes

China: Qing Dynasty Bonds

Parallel to the Russian case runs a dispute over Chinese imperial bonds. Bonds issued by the Qing dynasty between 1898 and 1911 have remained in technical default since 1939. A Noble Capital LLC lawsuit filed in 2023 was dismissed in September 2025.

Venezuela: When Debt Is Fresh

Venezuela defaulted in 2017, failing to service approximately sixty billion dollars in bonds. A federal court in Delaware authorized the sale of Citgo Petroleum to satisfy creditors. The difference is fundamental: Venezuela is the same state that incurred the debt; the bond documents provide for U.S. court jurisdiction; the assets are identified and attachable.

Turkey: How to Repay Imperial Debt

The Republic of Turkey assumed under the Treaty of Lausanne approximately one-third of the Ottoman foreign debt. The final payment was made in 1954—exactly one hundred years after the first loan. The Turkish case demonstrates that settling imperial debt requires political will on both sides and willingness to compromise—not unilateral creditor enforcement.

Forecast: What Happens Next with the Noble Capital Case?

The most likely outcome is dismissal at the pre-trial stage. Russia has announced that it will file a motion to dismiss, invoking:

- Sovereign immunity—tsarist bonds were sovereign acts

- Lack of legal succession—the Russian Federation does not inherit obligations repudiated in 1918

- Statute of limitations—claims are more than a century late

- Political question doctrine—the case concerns foreign relations committed to the executive branch

Yet for vulture funds, the outcome of the case is not the only measure of success. Protracted litigation generates headlines, attracts investor attention, builds negotiating position. And should geopolitical circumstances ever change and frozen Russian assets become accessible, a fund holding a final judgment will find itself in a privileged position.

Epilogue: The Limits of Law’s Dominion Over History

Tsar Nicholas II was executed in a basement in Yekaterinburg in July 1918—seven months after the repudiation decree was signed. His wife, five children, and four servants died with him. Their remains lay in an unmarked grave for decades, discovered only during the glasnost era.

The bonds bearing the imperial seal are now collectors’ items, sold at auction for a fraction of their face value as historical curiosities. Noble Capital acquired them for pennies, betting on a jackpot—not in the courtroom, but in a future contest over frozen Russian assets.

History closed its books on the Romanovs in 1918. Does the law possess the power to reopen them? The answer to that question may have consequences extending far beyond the fate of a single lawsuit—consequences for the future of three hundred billion dollars suspended in legal limbo between East and West.

The case is Noble Capital RSD LLC v. Russian Federation, No. 25-cv-1796, in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. As of January 2026, the litigation remains in its earliest procedural phase—service on the Russian defendants is being attempted through diplomatic channels.

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.